Uwe Henneken

"As a visual artist, creation is not just a profession but a profound responsibility—a duty and, at times, a burden—to be acutely aware of what we bring into existence."

Uwe Henneken’s work has been featured in solo exhibitions at Kunsthalle Gießen (2019); Centro Cultural Andratx (2018); Gesellschaft für Gegenwartskunst, Augsburg (2011); Kunstverein Braunschweig (2010); and Frans-Hals-Museum, Harlem (2007). Group exhibitions include Kunsthalle Bremen (2018); Kunstpalais Erlangen (2016); me Collectors Room, Berlin (2014); Kunsthalle Recklinghausen (2012); Musée d’art contemporain, Bordeaux (2011); ZKM Museum für Neue Kunst, Karlsruhe (2011); Arp Museum Rolandseck, Remagen, (2011); Lido Pavilion, 53th Venice Biennial, Venice (2009); Sprengel Museum, Hannover (2009) and Aspen Art Museum, Aspen (2007), among many more.

His work is held in the permanent collections of Kemper Art Museum, Saint Louis; Pinault Collection, Venice; Boros Collection, Berlin and Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich.

MEPAINTSME: Stepping back, where did your journey as an artist begin? Were you exposed to art at a young age? Was it something you always wanted to pursue?

UWE HENNEKEN: I grew up in a countryside village in the middle of Germany. There wasn’t much art around except for the imagery in the Catholic church. No one in my family had any real connection to art, and I often felt like an alien in that regard. As a kid, I read a lot and created my own dream worlds. I was drawn to symbolism and romanticism and always felt a deep calling for spiritual content, which I started exploring even as a teenager.

Interestingly, I wasn’t particularly drawn to making art at that time and only painted when it was required in school. My real passion lied in exploring historical contexts, our shared origins, and the cultural and spiritual connections that unite us. I dreamed of becoming an archaeologist and even studied it briefly alongside anthropology. Around that time, I started hanging out with friends from the art academy, and things began to shift.

MPM: That makes total sense when I look at your work. Was there a particular moment or circumstance that began that shift?

UH: Eventually, I realized that the prototype of the artist was the shaman—a figure who dives into different timelines and returns with visions to share with their community. That was when I heard the call to become an artist myself. With the help of an artist friend, we put together a portfolio and I entered the art academy.

MPM: Where you immediately drawn to painting?

UH: I felt, art is a service, much like the work of a shaman—something that uplifts, empowers, and inspires people. I wanted a medium that was universally accessible and resonated with people from all backgrounds. That’s how I arrived at oil on canvas, and I discovered I had a natural talent for it.

MPM: The visual world you create is constantly evolving. The backdrops and motifs change from series to series. Can you talk a bit about these stylistic developments in your work?

UH: I don’t care much about recognizability or signature pieces. For me, art should be unpredictable.

I remember being amazed the first time I saw a John Currin painting. But when I later saw a whole series of his work in a magazine, I was disappointed—they all felt the same to me, and I just got super bored.

In the past 15 years, the art world—especially the art market—has encouraged the tendency for artists to become one-trick ponies. Artists tend to create products, build an easy to recognize identity, and stick to a single formula. This was fueled by mega-galleries expanding globally and hunting for new markets, alongside art fairs popping up everywhere, and finally the rising dominance of a platform like Art Basel XYZ.

On top of that, the online habit of doom scrolling through images has reshaped how we perceive art, making it easier for AI to replicate and commodify creativity.

That said, this era definitely also has fascinating aspects, and there are some incredible artists thriving in it.

I’ve even fallen into these traps myself at times and I’ve learned the hard way to listen inwardly and trust what really needs to come through.

MPM: On the flip side, the constant influx of imagery from our phones has also made it more challenging to find that singular voice….

UH: I see artists as channels—mediums for one vast source of creativity. Ideas don’t truly belong to anyone; they emerge from a collective pool, waiting to be expressed. When I create a painting, I feel it flows through me, but is it really mine? We all build on what came before, often unconsciously.

What fascinates me is how the pace of creative evolution has accelerated. Early cave paintings remained stylistically consistent for tens of thousands of years, while human developments today evolve at lightning speed. It makes me wonder—to what point is this acceleration taking us?

For me, filtering inspiration is one of the hardest parts of the process. I have neurodiverse tendencies, where nearly everything can inspire me to an artwork, especially other art. Sometimes there’s so much coming in that it’s overwhelming and hard to focus on the work itself.

MPM: Your paintings have many divergences and it feels impossible to cover them all, so I’d like to ask you about some specific bodies of work and your feelings about them, beginning with one of my own particular favorites (titled?) Avatars and Padawans. How would you describe these primordial ‘creatures’ and where did they originate from?

UH: I absorb folklore wherever I can find it. What fascinates me is how stories and knowledge are passed down through generations—through songs, tales, and images that evolve as each person adds their own layer to them, making a new out of the old.

That’s how I worked for a long time, recomposing images, sampling, and remixing—practically a proto-AI. But at some point, I felt stuck in this method and wanted to break free. It coincided with a period of personal and external crises. I began transformational work with healers and therapy, and suddenly, I found myself drawing these creatures.

They’re apelike figures shedding their skins—multilayered scholars, getting aware that they are on a transformative journey, curious about where it will lead them.

MPM: There are many works that evoke other dimensions, where the inhabitants exist in almost an inverted painting history that coexists separately alongside our own. Can you talk a bit about this ?

UH: I’ve always been fascinated by history and art history. People often assume, because of my imagery and color palette, that I must have taken a lot of psychedelics. Fact is I never did. At some point I tried a bit, because people were talking about it all the time, but it didn’t have any remarkable effect on me. Maybe it’s just my neurodivergent perception, or maybe I “fell into the magic pot” like Obelix as a child.

I firmly believe we live in a multidimensional reality, with parallel timelines coexisting.

And I think we have the ability to choose the one we want to exist in.

MPM: Some of your work I find humorous in an absurd kind of way. Sometimes characters feel like they’ve just ‘appeared’ in their surroundings, very out of place and bewildered, others feel like they’re stranded or in some sort of hallucinogenic purgatory. Would it bother you if people see your paintings with a bit of humor?

UH: Not at all. The conditio humana is often absurdly grotesque, and many of my paintings reflect that. They capture the feeling of being lost in circumstances—whether it’s your family, surroundings, or even the body you find yourself in.

As a kid, I often felt like an alien—trapped in this earthly body, under these limited earthly conditions, surrounded by these strange humans. I tried to cope, to fit in, imitating, comparing myself—what a bizarre experience!

MPM: Yet common for many artists…..

UH: Over time, I’ve come to see this alienation as a lesson, a chance to learn and grow. Even if I fail, there’s progress, acceptance, and integration. Maybe one day I’ll figure out whether I’m just this super divergent dude or actually from one or another parallel dimension.

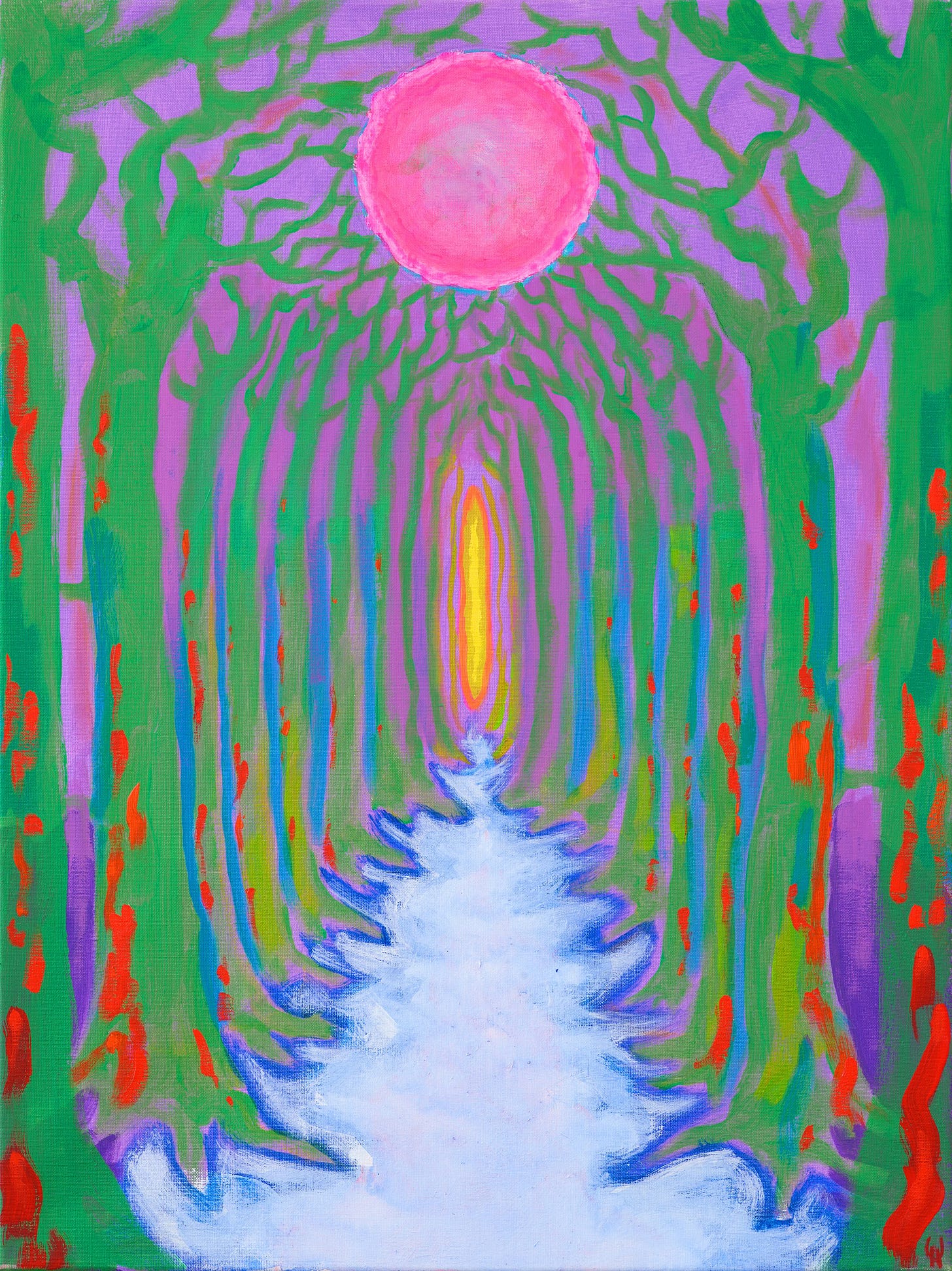

MPM: Towards the end of the last decade, you began exploring pure landscape, but more transcendental than observational. Many of these paintings evoke early 20th century artists like Redon and Hodler. Did this interest in less figurative and more landscape oriented painting coincide with your move to rural Denmark?

UH: Yes, as said, I am very open to inspiration, and especially discovering Redon was a blast of inspiration, even like a past-life-reconnection-kind-of-thing.

I often thought how it felt for the 19th century painters of the Hudson River School when they first took sight of a sunset in the North American wilderness.

Moving to this magical island in Denmark also had a huge impact. Although I’ve been painting colorful landscapes for over 20 years, I felt like I was truly seeing the colors in nature for the first time here. The purples in the soil, the blues and greens in the shadows, the pinks and turquoises in the sky mirroring in the sea—it’s awe inspiring.

MPM: A more recent motif are these beautiful chromatic variations of butterflies. Transformation has always been an important subtext in your work, correct?

Absolutely. We’re constantly transforming—physically, emotionally, and mentally. My paintings guide me in this process; I transform as they do.

The transition from caterpillar to butterfly is archetypical and fascinating, but what intrigues me even more is the butterfly’s transformation into the light.

MPM: Aside from the pure retinal delight, your brightly colored reinterpretations of art history could be read as a metaphor for the transformational power of art. Am I reading too much into it, or is it simply your love of color?

UH: It’s both—they’re interconnected. Color, like forms, symbols and archetypes, holds transformative and healing power.

I recently explored how Renaissance painters were initiated into these themes, learning to embed them in their work to create profound effects on viewers.

That connection has always existed—early humans didn’t venture into the deepest darkest depths of the caves to leave simple graffiti; their art had a deeper intention.

MPM: What are you currently working on in the studio?

UH: I just pulled a gigantic, unfinished 5-meter painting out of storage, and I’m excited to dive back into it.

MPM: As our world feels more and more like it’s teetering further and further toward the abyss (has it ever not felt this way?) I see your recent work as more optimistic? Do you agree with this sentiment?

UH: Art should disturb, make you reflect about the state you’re in and push boundaries, but it should also uplift, inspire, and empower, touch and give hope.

In my experience, we humans shape our reality through our thoughts and actions. As a visual artist, creation is not just a profession but a profound responsibility—a duty and, at times, a burden—to be acutely aware of what we bring into existence. What we create influences the world, becomes part of reality, and resonates with others who interact with it. It’s a deeply serious undertaking.

Ultimately, no matter how challenging or desperate a situation may seem—whether on a personal, global, or even universal level—it is all part of a greater process of transformation.

But as long as humans exist, there will be cave paintings, carvings, dance, sound, and rhythm.

MPM: Thank you so much for taking the time to speak. Do you have any shows coming up that you’d like to mention?

UH: Among the upcoming projects, the one closest to my heart is a group show curated by Kathryn Lynch at Maya Frodeman Gallery in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. It’s set in one of the most inspiring landscapes I’ve ever dreamed of showing in.

Also next year, I’ll embark on a transformative two-year journey with Thomas Hübl's Timeless Wisdom Training, and I’m excited to see where it will lead me.

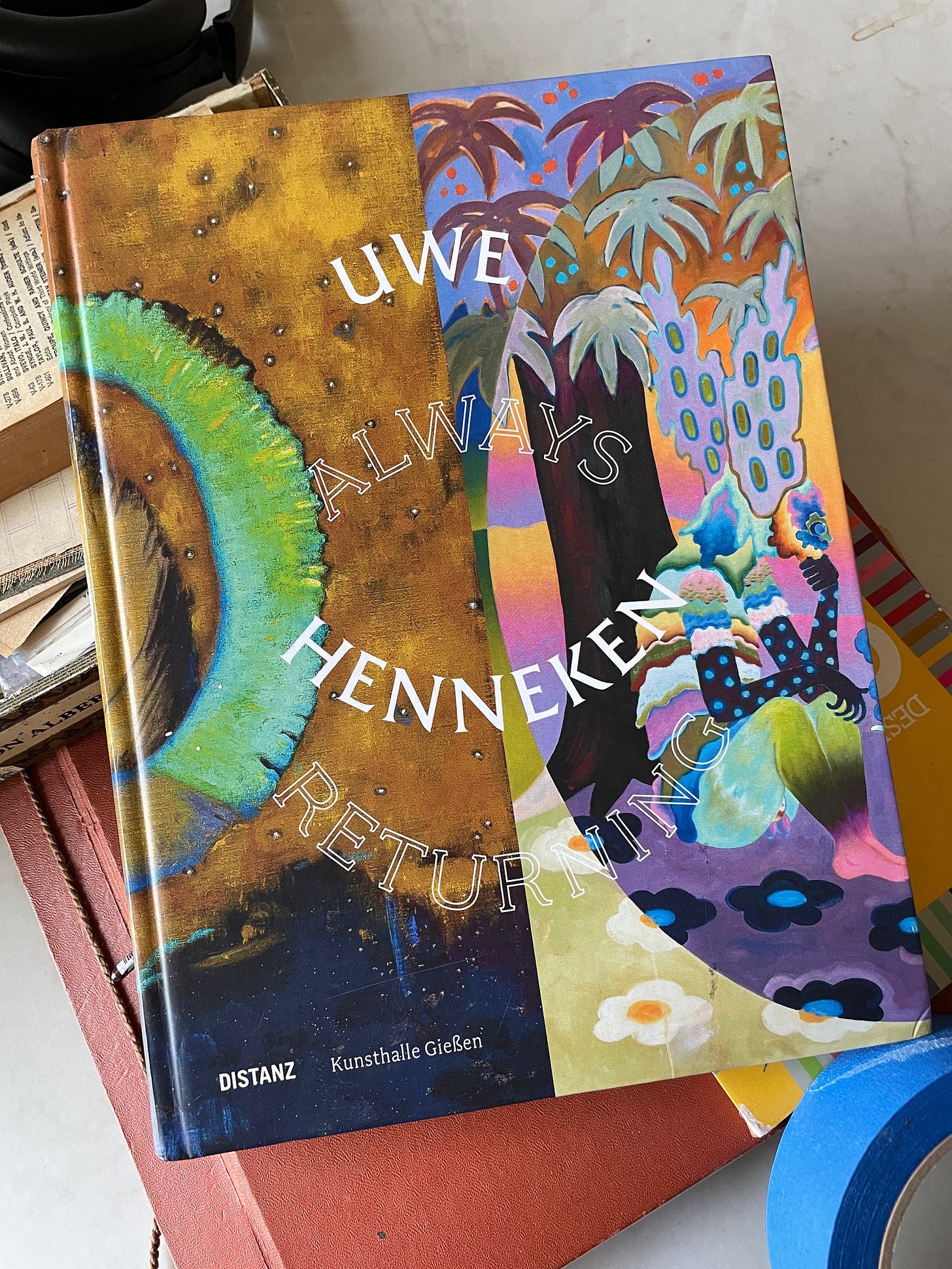

A beautiful monograph of Uwe Henneken’s work is currently available at bookshop.org and Amazon. #affilatelinks

Always Returning documents Uwe Henneken's artistically multifaceted development since 2010; it is published on the occasion of the eponymous solo exhibition at Kunsthalle Gießen (2019). Katja Burggräfe, Uwe Henneken, Nadia Ismail, and Astrid Legge contributed texts and interviews.

Really enjoyed this read. Beautiful.