Ross Simonini

"I like when one art form contradicts another and when different works reveal hidden sides of the artist."

Ross Simonini is an interdisciplinary artist, writer, and musician. He has held solo presentations of his work at the Sharjah Biennial (UAE), Francois Ghebaly (NYC), anonymous gallery (NYC), Et Al (SF), SHRINE (LA), suns.works (Zurich), Shoot the Lobster (LU), and Human Resources (LA). His novel, The Book of Formation (2018, Melville House) chronicles the rise of a fictional philosophical movement. He releases music under his own name and has previously released music as a member of the bands NewVillager and Trespassers William. He has performed at Performa, Andy Warhol Museum and the Brooklyn Museum.

MEPAINTSME: Our interview was put on hold because your life has recently been upended. Your home, studio, and artwork were all destroyed in the L.A. wildfires. Luckily you and family are safe, but I know you’ve had to relocate multiple times in the last few months since the fire, only recently finding a longer-term stay in Santa Barbara, about 2 hours out of LA. Did you manage to salvage anything or is it pretty much like starting over for you and your family?

ROSS SIMONINI: We’re starting over, at least in the material sense. On the night of the fire, we evacuated with a full car (wife, dog, infant, infant accoutrement, dog food) so I didn’t manage to take many personal things: an armful of outfits, hard drives, and folders of drawings. At that moment, I was not thinking our house would burn down, so I took no paintings or instruments or books or mementos. I lost about 500 artworks, including dozens of brand-new unseen paintings, all my journals, and most of my life’s work so far. In other words, my past has been largely erased. Back to tabula rasa.

MPM: How have you processed the destruction of so much of your creative output all at once?

RS: I never know what it means to process an experience, especially one like this, which will ripple through my life for a long time. When is an experience processed? Hard to say. Art is probably my primary mode of processing life, but it works at the unconscious level. For me, intense experiences often manifest as physical pain, so I’ve been trying different modalities for working on the body: EMDR and P-DTR and NKT. I also think of art as a form of physiological process, something inherently biological, which is about movement or touch or sensation. When I paint with my feet, for example, I want to look at the world through my proprioception, not just through my eyes. I am trying to feel the word. This can help. Emotions are abstract and non-linear, so working with something palpable keeps me grounded throughout it all.

MPM: Do you anticipate a shift in your practice from this experience?

RS: How could it not? I’ve been thinking about other artists who went through similar experiences. Jack Whitten’s studio burnt down in the 80s and he didn’t show work for several years after. When he re-emerged, he had invented his innovative tiled painting style. Rudolf Steiner’s Goetheanum — a huge wooden temple — was burnt by arsonists. He rebuilt it with concrete, so it would be robust against future fires. I don’t know how my work will shift, but the fire is undeniably transforming me, so I’m sure the work will change too.

MPM: I saw on your instagram a triptych in progress (or completed) that was destroyed in the fire, titled Levities, which was presented like an altarpiece. It seems different formally, perhaps more somber. Were these part of a larger body of work? Can you talk about this group?

RS: Yes. There were about a dozen works destroyed in the Levities series. I imagined them as towers of upward-moving energy, expressions of levity. It’s the kind of movement that draws water up from the ground, through the roots and to the tops of trees — the opposite of gravity. I was also thinking about the concept of kundalini, where a serpentine life force travels up our spine to the crown and inspires a spiritual awakening. Some people regard this motion of energy as the purpose of every religion on earth.

There’s also the levity of humor: making light of reality or making reality lighter, which is something that I always value in my life. It’s rare that art makes me laugh or compulsively smile and I’m grateful for anything that accomplishes this. In the canon of art, I rarely see this kind levity. There’s a belief that serious art should be serious in attitude. I think this is why comedies almost never win Oscars, or why goofiness is generally not a mode associated with important art. I certainly enjoy intense, dark art, but I don’t think it is the measure of greatness. In a funny twist, I think it’s exactly this kind of over-serious attitude that makes contemporary art laughable to the rest of the world. I rarely see a film or read a book in which a gallery, museum or artwork is mentioned without some snide jab about its pretentiousness. A little levity does everyone good.

MPM: You studied music at the University of California and then earned a masters in writing from Bennington. When did painting begin? What about your involvement with the art world in general?

RS: Like most people, I started drawing as an infant, long before I wrote or studied music. Since then, I’ve never stopped drawing, but I did not consider it a vocation until much later. I thought about it more like scribbling and doodling, which I don’t mean in any kind of pejorative way. Doodling is an unconscious urge. It gives a space to explore the hand and gives form to mental projections. I wanted to keep the space of art loose like this — light and un-serious — while continuing to practice it. That way, it filled a different function in my life than school.

I was always interested in learning about art and artists, but I was never interested in art school. I’ve only taken one art class and it was not for me. With music it was different: I wanted to learn all the deep theoretical, mathematical systems. And writing is built on the system of grammar, usage, and language, so I was happy to go to school for those art forms. But I wanted to develop visual art outside of systems, to have some part of what I did that was free from that type of intellectual intervention.

(All that said, both of the university programs I was in were fairly experimental and open types of programs, and even then, I didn’t love the results. I would prefer education as a space for simply exposing students to art, rather than directing, judging, and comparing.)

I made what I consider to be my first painting at the age of 27. It was an image of Saint Francis and the Wolf of Gubbio, which is a myth that has lived in my imagination since I can remember. I showed that painting, and some other early work at a restaurant in Oakland, California alongside some paintings by the late writer, William Saroyan.

Around that time, I was in a band called NewVillager, which functioned like an art collective. We created multidisciplinary events with many collaborators and a lot of them occurred in galleries and museums: Human Resources in LA, The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Jack Hanley Gallery in NY, which naturally led to working in other art spaces. When that project ended, I began to focus on my own work.

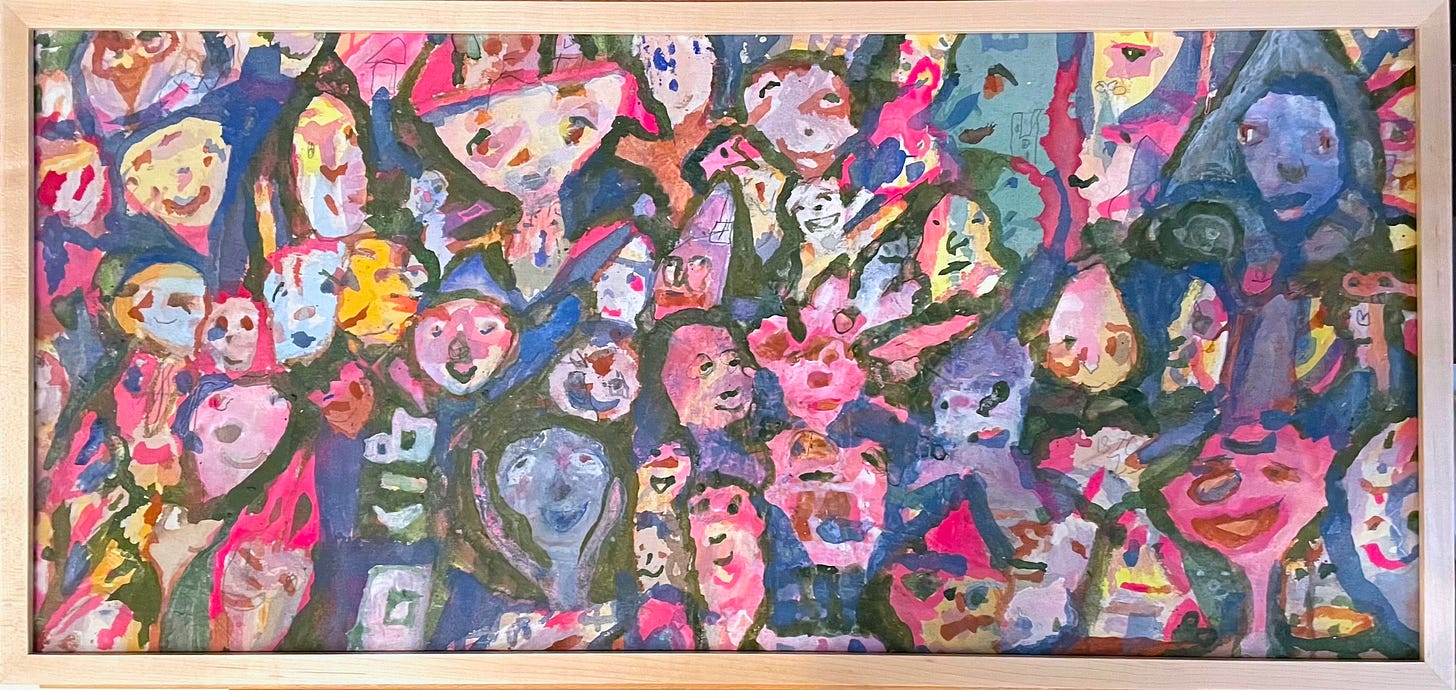

MPM: Your use of repetition when depicting faces, along with your palette which is very light, translucent and ethereal, feels akin to spiritually meditative techniques. Is painting, for you, analogous to the practice of meditation?

Meditation is important to me, certainly, but I would say the state of mind I live for is the creative trance — the feeling of falling into an artwork. I think both states have similarities and I’ve certainly thought about that connection. Making art, like meditation, tends to focus on repetitive activity. For a few years, I was working with refrains in my work, including painting and music and writing. It’s like the way people might use an affirmation or mantra or prayer. If you write or speak a phrase enough times, the language embeds itself into you, deep down. Eventually, it begins to repeat in your mind without effort. It lives inside of you. When I was working on this, I’d consider many phrases, changing the words and ordering until I landed on a kind of refined language technology. As a writer, I found this fun: how can language be maximally efficient? How can I most directly communicate with my subconscious? Once I landed on a phrase, I began painting by using those words, so that every mark was a letter. They were not legible to anyone, and you wouldn’t recognize them as words, but the method maintained my focus, allowed new types of mark making, and was very effective at placing me into the trance. I have an album of music titled Refrains which borrows on this same technique, which I now use as one of many methods in my work. The refrain is one of many colors.

MPM: I was trying to find threads between your painting and your music. Are they conceptually independent of one another? Can you talk about what kind of relationship you think they have?

RS: Beyond the methods, which do overlap, I’ve heard some people make connections between the faces in the work and the voices in the music. I’ve also heard the word “ethereal” dropped regarding both forms, as you mentioned above. Those connections make sense to me but I did not intentionally think about them. It’s certainly convenient when an artist’s interdisciplinary aesthetics all line up. It makes it easier to understand what an artist is doing if everything lives in the same world. But I particularly love artists whose work isn’t so tidy. It forces me to find new kinds of connections beneath the surface. I also like seeing the full, complicated person. I like when one art form contradicts another and when different works reveal hidden sides of the artist. That feels more honest to my experience of life, which is so manifold and complex. Pain, joy, repulsion, beauty, tragedy, comedy. I’d like to express all of it.

MPM: I’m curious about your use of milk paint and egg tempera as painting mediums. Are there reasons outside of their non-toxicity and physical properties that have made these your chosen materials?

RS: For me, the physical properties suggest energetic properties to these substances. Milk and egg are two of the fundamental materials of animal life, and I build my work from these elements because I want the work to be a transference of life force. I also use watercolor (made from gum arabic, which is sap, another substance of life) for the same reasons. Art is most successful to me when it expresses vitality, and using vital materials is a good starting point.

MPM: Without a studio, are you currently working on anything? If not, what could you see as your next project?

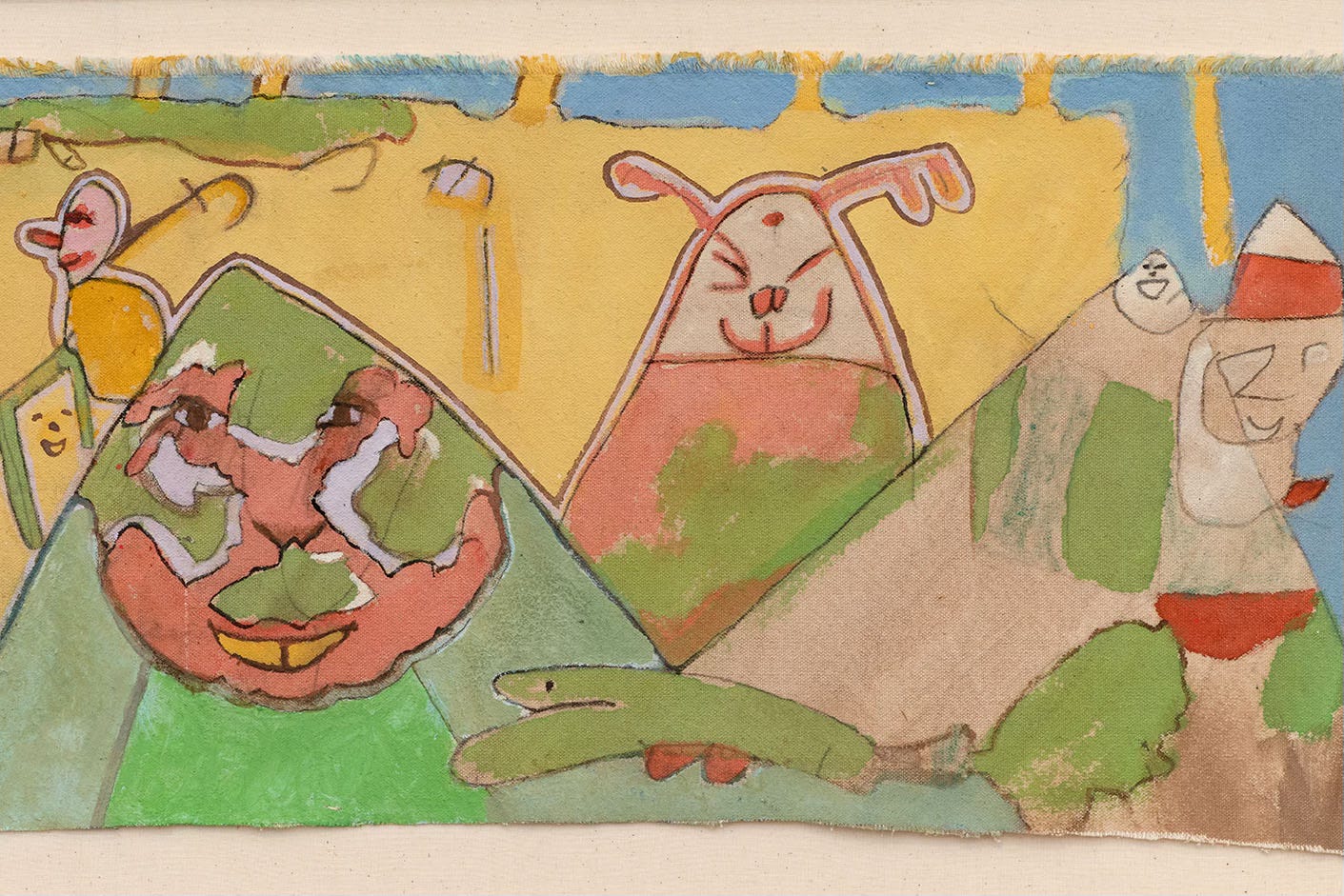

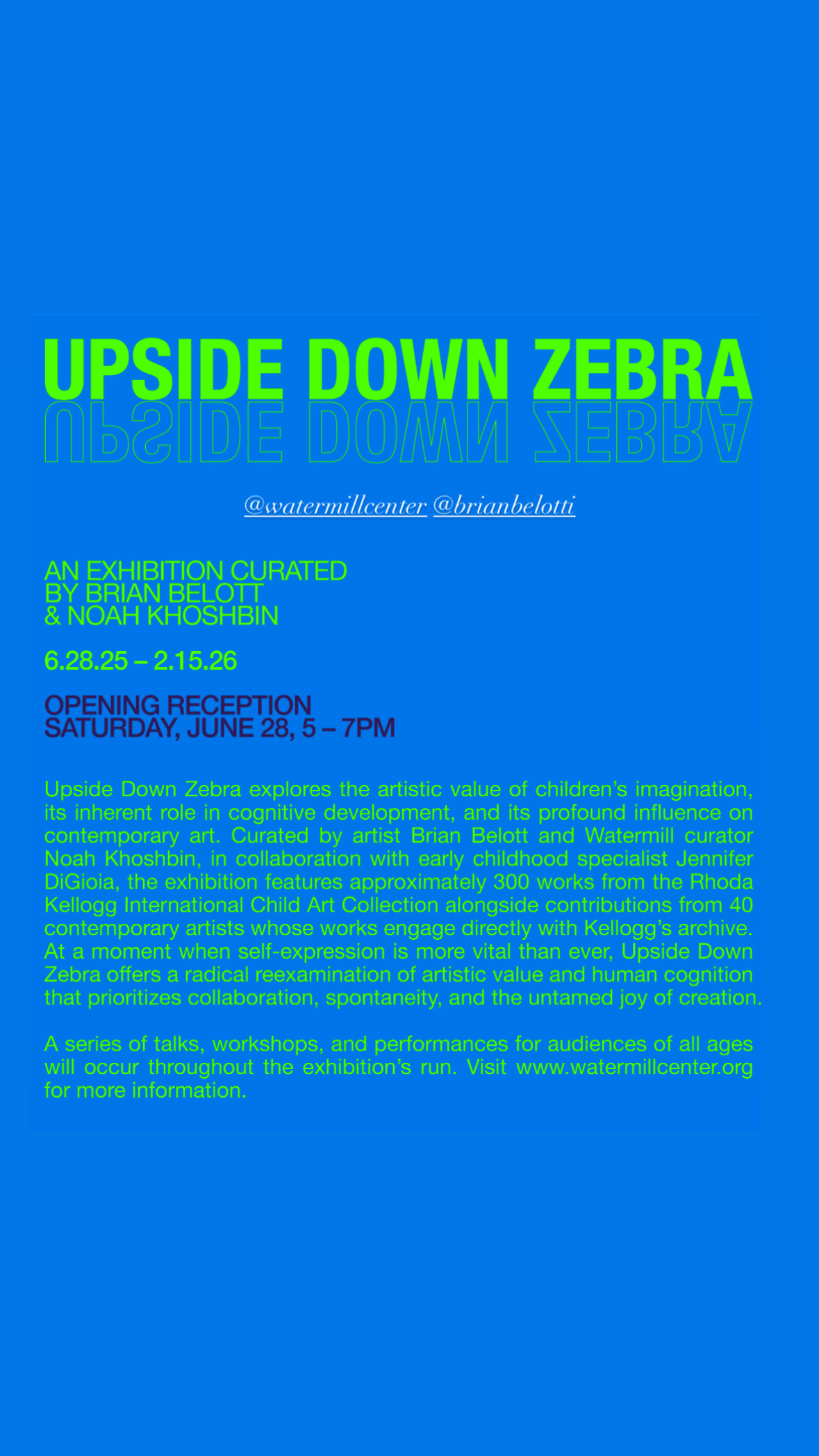

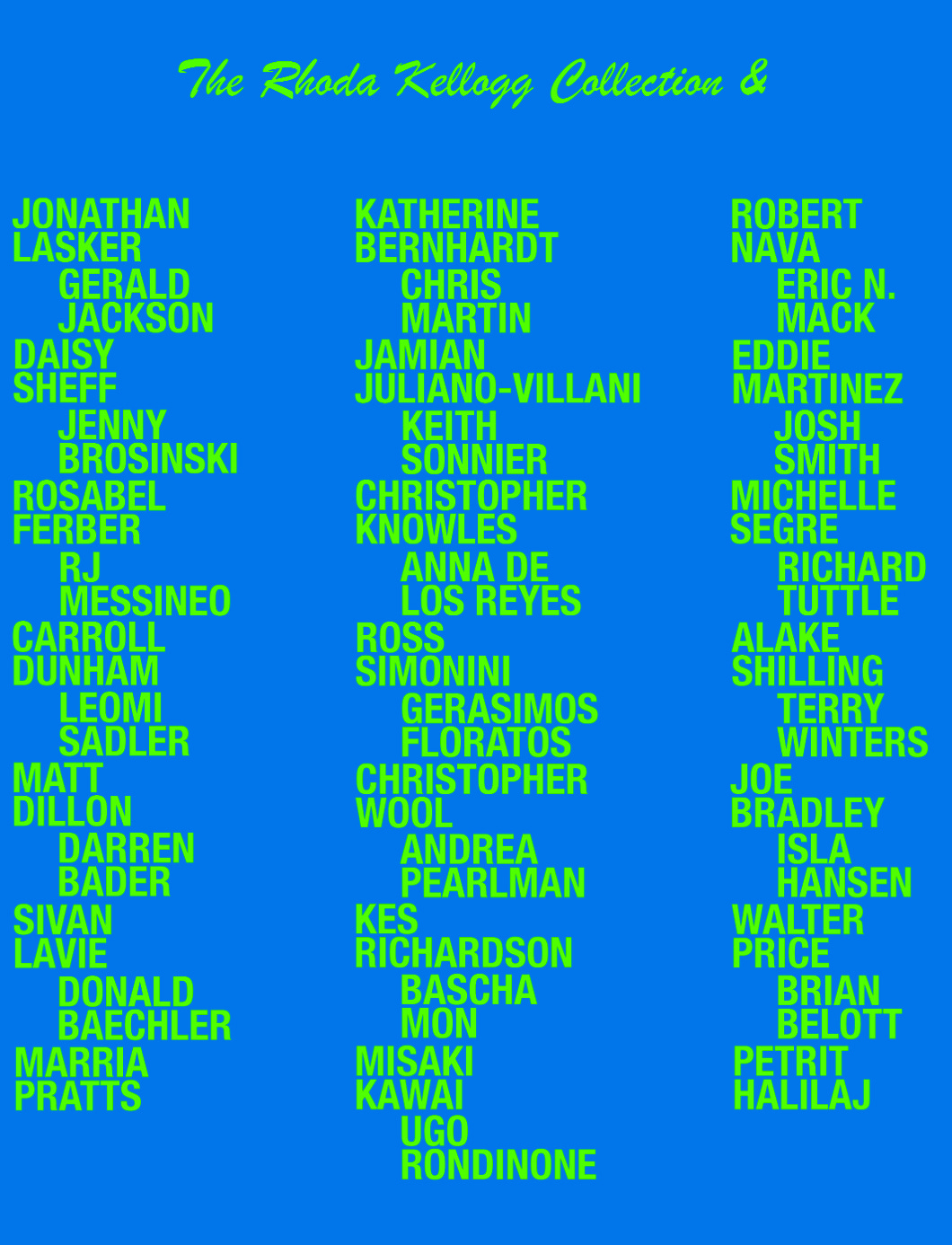

RS: I did not have a studio for four months after the fire. During that time, I made very little art. We were moving around often and raising an infant. I wrote a few essays and focused on releasing some music, which I had made over the last few years. I recently found a studio, and I have just completed one work, which is for a show about children’s art at the Watermill Center in New York. It relates to my old work, certainly, but it’s also its own thing, specific to the show. It’s been useful to have an assignment like that, which doesn’t require me to ask me to immediately establish an entire new body of work. I think that will take some time.

MPM: What are your overall aspirations with painting?

RS: To create joy and pleasure and mystery, both for me and for viewers. But on a deeper level, I believe art is about love. Through experiences of joy and pleasure and mystery, I have fallen in love with art many times. Not just with the physical paintings but with the vital force that those works transmit. And connecting with another life is, for me, what saves me. It’s what keeps me free from getting caught up in nihilism and religion and money obsession and meritocracy and all the other traps of society. Offering this connection is what other artists have done for me and I am extremely grateful for it. It’s one of the few things that gives me real energy to live well. I hope, in my life, I can pass that on.

MPM: Thank you for your time, Ross, and best wishes to you and your family.

More on Ross Simoni

rosssimonini.com

rosssimonini.substack.com

instagram.com/rosssimonini

Ross Simonini Music

The video Theme of No Pity

Forthcoming Exhibition at Watermill Center, NY

This was a real treat. It really stirred and fed my creative curiosity. I was not familiar with Ross Simonini - thank you for the introduction.