MEPAINTSME

"Drawing has always been difficult for me. I have a certain degree of facility, but the process of arriving at something that I feel good about is harrowing..”

Mepaintsme is an artist and curator living in Asheville, NC and holds a BFA in painting from the Maryland Institute College of Art. After living and working in New York City as both a painter and editorial illustrator, he relocated with his family to Asheville where he began a daily curation of art postings on his Instagram feed through the anonymous surname @mepaintsme. With a propensity to focus on history’s creative outliers, he quickly developed a loyal following of artists, writers, and musicians that has grown to over 260k followers. @mepaintme has been praised by such art world notables as Jerry Saltz, Peter Libby of The New York Times, and the London Paint Club.

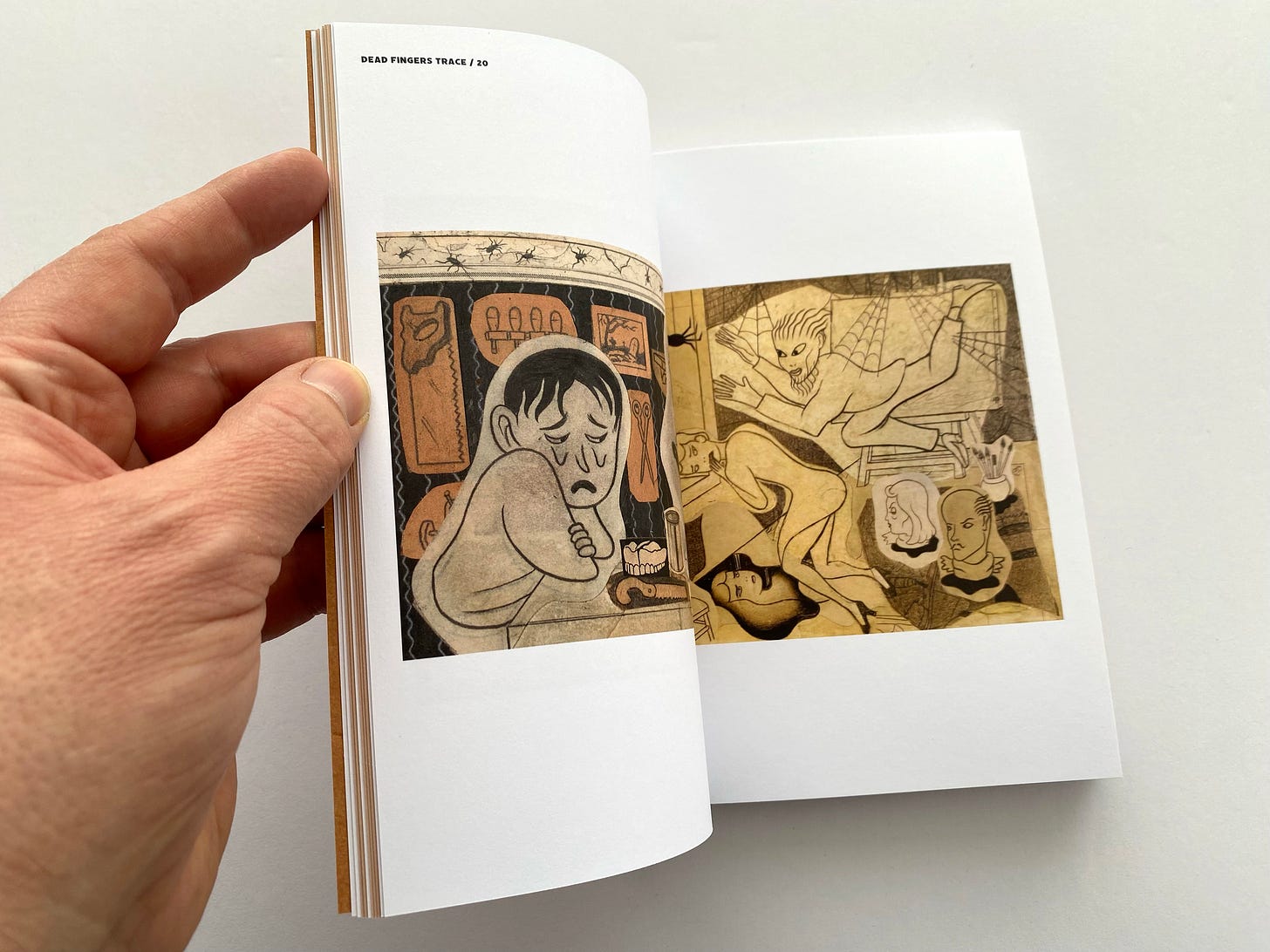

The following interview is an excerpt from the artist’s new monograph Dead Finger’s Trace and was conducted by publisher Ryan Standfest of Rotland Press

Ryan Standfest: Could you describe your studio set-up?

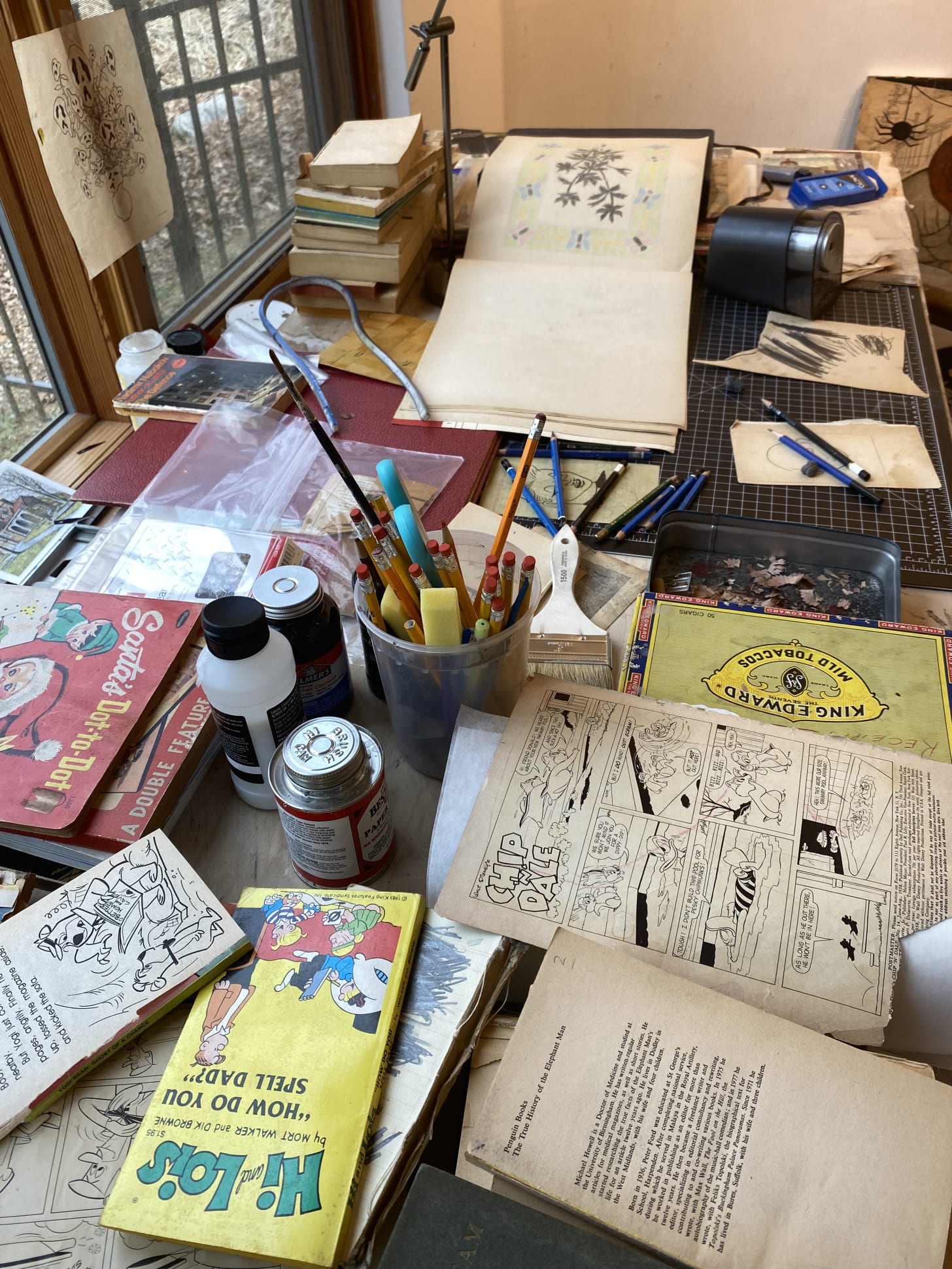

MEPAINTSME: My studio is about 400 square feet, with glass windows that run the length of the northern side. Running the length of the windows are long wooden tables, as well as another table along one of the four walls. The tables I built are extremely important to the way I work because I’m incredibly disorganized and need to spread most of my materials across all the tables. They’re as much an organizing component as they are a place to work. Another wall has built-in shelving that holds a lot of materials and books. The bookshelves are my favorite because I was able to design them to hold all the different sizes of my art books, which I never had before. I also have a plain wall that I use to work on, and for viewing finished work.

RS: How does your curatorial activity grow out of your studio work and your studio work out of your curatorial activity?

MPM: In regard to my Instagram account, whatever I’m currently working on in the studio often creates the impulse for what I may choose to curate on Mepaintsme. If I’m working on something narrative, undoubtedly my curatorial choices begin with narrative concerns, yet through the course of researching a narrative painting, for example, something in that painting may spark a very strong formal reaction, which takes my interest in a different direction, leading to subsequent choices that are unexpected. The process is cyclical because I may take those curatorial choices that have led me down a very different path from where I started, and look at what I’m working on in the studio a bit differently. Since I’m posting 5–6 works daily on Instagram, it’s inevitable that my curatorial choices affect my own work in some fashion, and vice versa. Outside of Instagram, my curatorial process at my gallery or other projects is quite independent from my own practice.

RS: What do you collect? How does your collecting relate to your work?

MPM: I’ve always been an avid collector. For most of my adult life, it’s generally been art books, records, magazines, toys, and general ephemera, but since I began my Instagram feed, and subsequently the gallery, I’ve begun constructing a small yet potent art collection. Some of the art is purchased, and some I’ve come to through trades or gifts. My partner and I keep work that we acquire together in our home, but any work that is more to my own taste I hang in the studio. Outside of fine art, I tend to collect things that have some sort of personal meaning to me. I have a large number of old comics that I acquired from my grandmother (they belonged mostly to my aunts and uncles from when they were kids), but I also collect old crime magazines and books from the late 40s and 50s, old children’s books, coloring books, trading cards, puzzles, newspaper comics, as well as my own artwork from when I was a child. I guess I’m a hoarder at heart, but I’m not very good at keeping what I’m hoarding in the best of shape, so sometimes things end up destroyed over time. I have a few interesting items that are unique—like two small personal address/appointment books that belonged to the French Cubist Jacques Lipchitz, as well as an old wooden maquette table from his studio, which I treasure. I also have a dozen or so small pieces of a painting by Helen Frankenthaler that I saved from the dumpster when I was working for her as a studio assistant (none of which are signed, so they are worthless beyond my own personal history with them).

RS: Describe a formative non-art experience that helped to steer you toward your role as an artist.

MPM: That’s difficult, because I’ve been around art my entire life and there was never anything else I planned on doing. I had a good friend whom I met in my freshman year of high school who had a real influence on me creatively, in regard to music and culture. He was a senior and was the first person I ever knew who really lived life by his own rules. He drove to school in a hearse and dressed in mod suits and Beatle boots. He introduced me to punk rock, as well as ’60s psychedelic and garage bands. He was a complete oddball and outcast, but sort of floated above it all in a cool way. I can’t say he steered me to becoming an artist because I was already on that trajectory, but he was a huge influence on me in every other way.

RS: Additionally, describe a formative art-related experience that helped cultivate artistic identity.

MPM: My closest friend, whom I moved to NYC with and lived with for our first four years, had a real understanding of painting from both a spiritual and technical standpoint that was very influential to me. He had artistic concerns that were completely outside of what would be considered by someone who sought a “professional” career. He was antisocial, argumentative, and had disdain for most artists. He was also autistic, which at the time neither he nor I were aware of. It was only about 25 years later that he was diagnosed, and it clarified a lot of his behaviors that were very difficult to live with at the time. In many ways, he created new pathways in my understanding of what art is and what makes it meaningful. At the same time, he also cultivated in me a lot of negative feelings about people and attitudes toward being an “artist,” which, in retrospect, were not always healthy. This many years later, I’m still sort of processing our friendship.

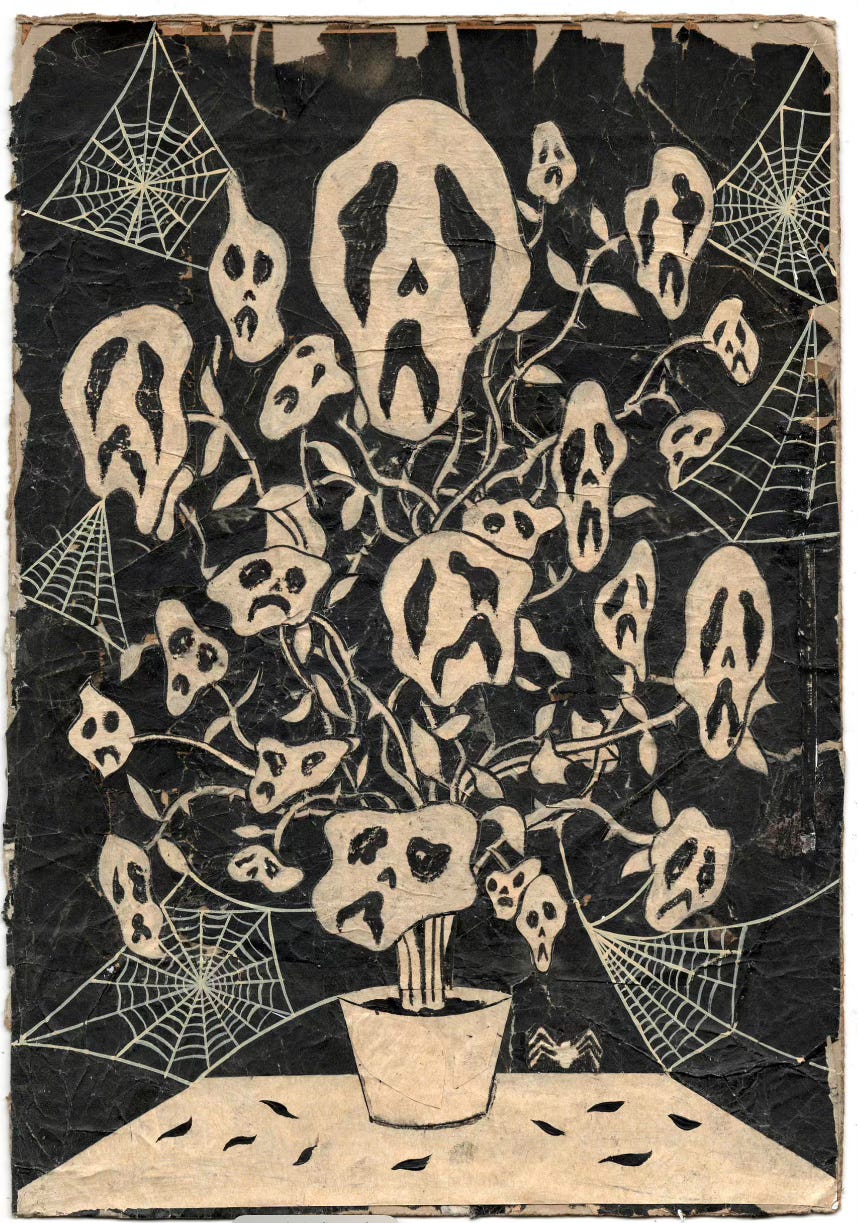

RS: How did you arrive at the medium you’ve chosen to work in?

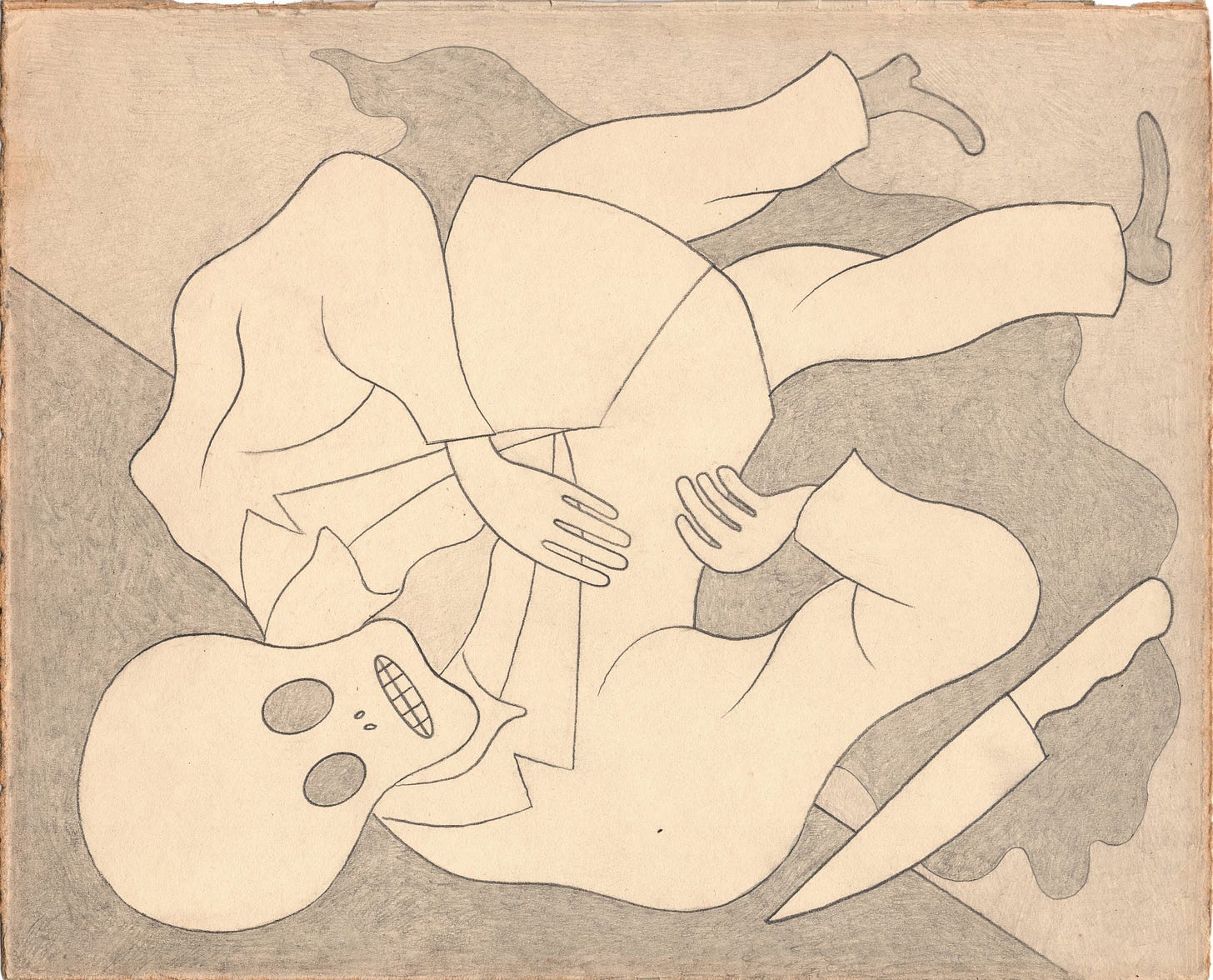

MPM: Drawing has always been difficult for me. I have a certain degree of facility, but the process of arriving at something that I feel good about is harrowing, as opposed to painting, which feels very natural to the way my brain operates. However, a few years ago I became stuck in a rut with what I was painting and thought it would be an interesting challenge to create a body of work that took on those problems I had with drawing head-on, sort of confronting my fears. I literally put my oil paints and brushes in a box on the shelf and began drawing exclusively. I think that’s why a lot of my work from those first couple of years has a painter’s sensibility—there were so many other considerations (collage, texture) beyond simple, unadulterated line.

RS: Your drawings are very tactile and respond to the ephemeral nature of aging paper and print media. What does it mean to you that your primary audience has been receiving these images as digital photos, backlit, transmitted on phone and laptop screens, often at a greatly reduced scale?

MPM: This is a fairly standard concern for artists, I suppose. For me, the larger issue isn’t so much how the work translates digitally, but the risk of overexposure and the way that can diminish art’s power and physical presence in the real world. I’m very aware of how the work reads online, and since I tend to work on a small scale, it usually translates reasonably well. Still, any time a work is reproduced or seen as a 1 x 1 inch digital image, something gets lost—artists have been grappling with that for generations.

Overall, though, the way we consume art now is a huge improvement over the alternatives of the past. Books I treasured in college as “primo” reproductions look terrible by comparison today. Sometimes I wonder if it might even have been better 80 years ago, when art books and magazines reproduced images only in black and white—at least then, more was left to the imagination.

Order your copy of Dead Finger’s Trace + Vatis Species from Rotland Press here

True insights into the things that influence his art...very interesting that so many influences come from such diverse life experiences, and various times in his life.

Hey Joel, great to see you on here! From Sophie (@duez_art)