María Korol

"The connection between gesture, body language, and psychology is expressed strongly in my artwork, where a quick, simple line can describe a whole character’s mood with great economy of mark. "

María Korol's artistic practice is rooted in drawing and painting. She is interested in storytelling, literature in conversation with history, memory, and transformation. Born in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1980, in the middle of a military dictatorship, she grew up in Brazil for about five years and later returned to her home country. She moved to the United States in 2004. Korol has shown her artwork nationally and internationally in places such as March Gallery and The Painting Center in New York City, Institute 193 in Lexington, KY, Marcia Wood Gallery in Atlanta, Cluster Contemporary in Rome, Italy, and the Akademie der Künste in Berlin, among other places. Her artwork is in numerous collections. She is a distinguished fellow of the Junge Akademie der Künste, the Hambidge Center, and the Women's Art Institute. In recent years she was a finalist for the Atlanta Artadia Award and the recipient of the Edge Award with the Forward Arts Foundation. Her work has been mentioned in The New York Times, ARTFORUM, ART PAPERS, Burnaway, and ArtsATL. Her studio is based in Atlanta, Georgia, where she is an assistant professor of art at Morehouse College.

MEPAINTSME: You were born in Argentina and into a rather painful and chaotic childhood that shaped both you and your practice. Can you talk a bit about this period of your life and how it may have influenced your work emotionally or conceptually?

Maria Korol: I grew up in a dangerous environment in many ways: Argentina was in the middle of a murderous dictatorship that went from 1976 until 1983 and that “disappeared” 30,000 people. My parents were very young (18 and 19 years old) and formed part of the resistance to fascism, which made them targets. They left for Brazil for about five years, with me as a newborn baby, and there was turmoil and drama between them, and between them and their families. My childhood was marked by unpredictable events and instability. At age six, when it was time for me to start elementary school, my parents went back to Buenos Aires, Argentina, and after about two years they split permanently. I started jumping back and forth between living with one or the other, changing houses and schools every two to three years.

I would form strong sisterhood bonds with my girlfriends at school, and I would spend more nights in any given week sleeping at my friend’s house instead of my mother’s or father’s place. I took refuge in these friendships, in school, in adopting street cats, and in reading. At age eight, when I changed schools for the first time, I had an incredible teacher, Rubén Profitos, who gave me books. To this day, I must have a great book to read in order to feel like my life is on the right track.

The benefit of growing up in this environment was that I learned to take care of myself early and to self-preserve, becoming acutely aware of body language, gesture, and expression in others so that I could accurately perceive good and bad intentions and assess a person’s overall quality. Then, when I was thirteen, I started studying classical and modern dance, learning more about the embodiment of inner life and the body’s capacity to tell stories and reveal personality. The connection between gesture, body language, and psychology is expressed strongly in my artwork, where a quick, simple line can describe a whole character’s mood with great economy of mark. I am drawn to images that suggest a loose narrative: I prefer stories that raise questions which can be answered in more than one way, ambiguity also in the sense that, as hard as you might try, you cannot ever fully know a character or a person—especially in a drawn image, a photograph, or even a film—but a lot can be suggested through expression, gesture, and action.

MPM: These early experiences later became the basis for a large series of ink drawings depicting interfamily dramas. These semi-autobiographical works are brutally honest, touching on a wide range of emotions and trauma, and depict real families in real spaces. Can you talk a bit about how these works came about?

MK: The series titled A place where twisted people live, and every day is the same day comprises about fifty ink-on-Stonehenge-paper drawings, each 22 x 30 inches, mixing personal memories with history and fiction. It is one of my all-time favorite series of drawings. I started making them in 2014 and continued over the years, never discarding the possibility of adding more drawings whenever I feel compelled to make one. As you say, they can be brutally honest in terms of the situations portrayed and the interpersonal dynamics between the characters, but it is a satire, so the “brutality” is balanced with humor, a true coping skill for many Latin Americans.

The first drawings I made for this series came out of frustration with oil painting. I think frustration can be a great creative force, often underappreciated. I was struggling with a painting, trying to figure out a composition for a Sunday family gathering scene that I wanted to get out of my memory and make into an image. In a moment of defeat, I abandoned the painting I had been working on for days and turned to ink on paper to work much faster—as an exhalation instead of a planned, labor-intensive process, which a painting often demands, at least for me. I drew a scene using ink on paper in a spontaneous way, without any sketches, rendering a grandmother bringing food to the table while a girlfriend and a daughter compete for the father-figure’s attention: he is the center of everyone’s world; everything revolves around him; three generations of women are trying to please him. While this domestic scene is unfolding, a bird is thrusting itself onto the windowpane, creating a sense of urgency and adding an anxious mood.

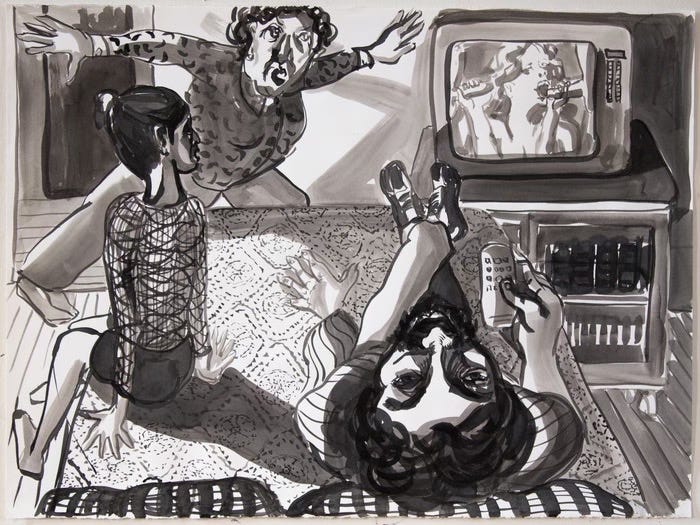

After that, I made another drawing, titled El porno de papi (Daddy’s Porn), portraying a father checking out a pornographic movie with the daughter next to him, while the grandmother enters the room, almost flying, to turn off the movie. It took me some time to understand the strength of these drawings, but I knew that I was up to something because I continued making them compulsively over the following days, and over the years.

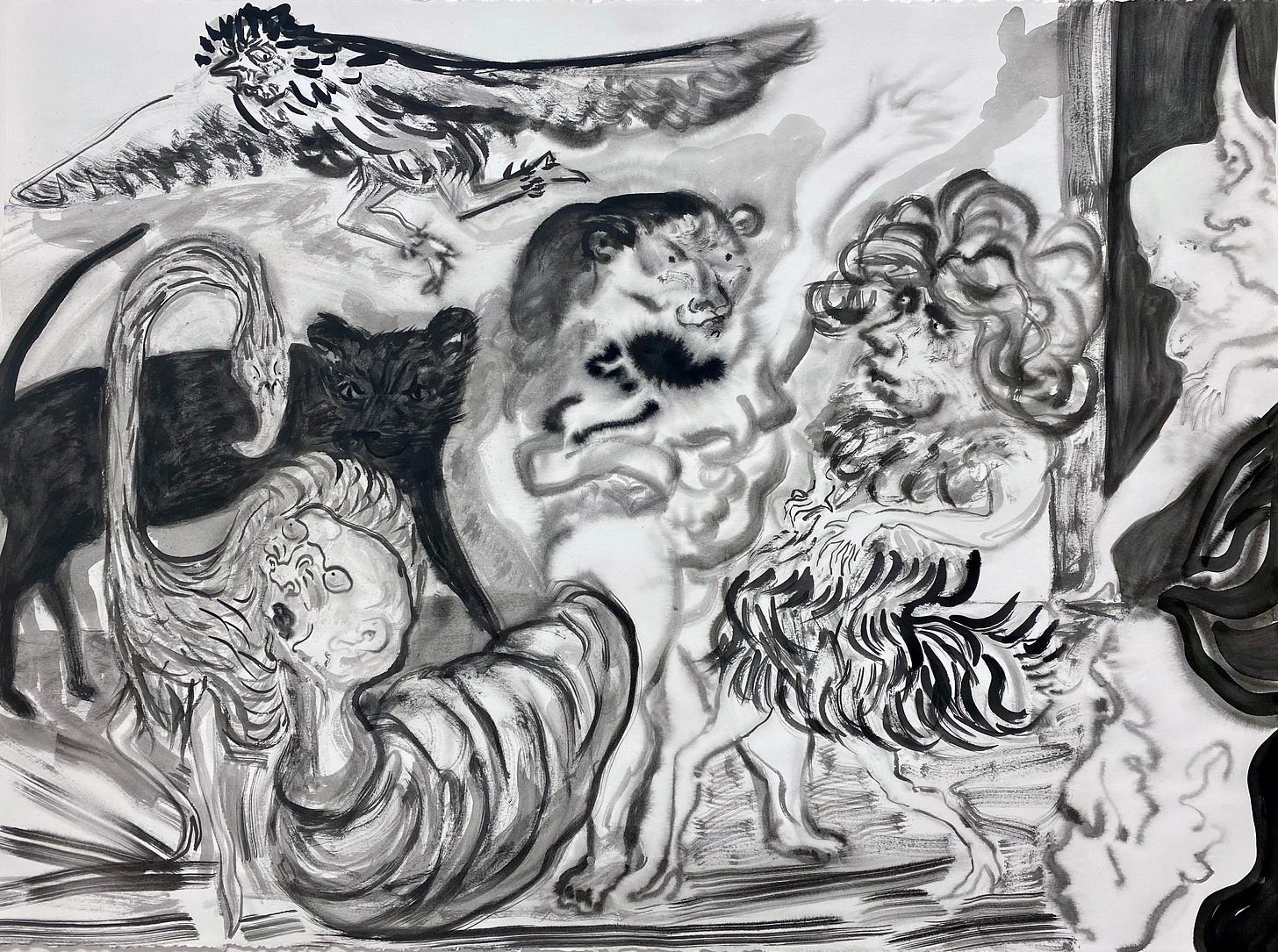

MPM: Over time, your focus shifted from real human situations into more fantasy worlds populated by chimeric and therianthropic figures. Many of these strange creatures feel like they could have stepped straight out of a Bosch painting, yet there’s a playful, almost mischievous humor to them—standing upright, wearing high heels, performing social rituals. What fascinated you about giving animals such clearly human behaviors?

MK: Animals had often featured in my compositions parallel to human figures, but the turn to full-on anthropomorphism started in 2023 when, after about ten years of just drawing, I turned back to oil painting to give it a second chance. I made a series of oil-on-linen paintings while I attended an artist residency named Cobertizo in Jilotepec, about an hour and a half north of Mexico City, in a pastoral setting, with a studio across a pond full of birds and fish. There were also two cows on the grounds and several dogs—Ofelia and Tomás were my favorite ones.

I was part of a cohort of eight artists, and together with the residency team and the guest speakers, we were in an intensely social atmosphere, full of artists’ egos and a variety of personalities to observe. I was also speaking Spanish more than usual, as I live in the United States now, so I was reacting to sound and to language in a profound way, reflecting on how communication happens through sound and also through movement and looking. I was observing all the animals around me and re-centering my attention on them—purposefully, to avoid the humans sometimes—seeing that the animals too were interacting and communicating, just like we do.

Right before going to this residency, I had visited the Biblioteca Palafoxiana in Puebla, the first library in the Americas. They had two incredible books on display, Arca Noë and Musurgia Universalis, by Athanasius Kircher, a German scholar from the sixteenth century. These two books deal with animals in different ways, each containing incredible fantastical illustrations that, at the time the books were created, people took to be accurate depictions of animal species (I suppose), but they were clearly imagined by Kircher. Seeing these illustrations and being surrounded by nature, the sounds of animals, and my artists’ cohort inspired me to make a series of paintings and drawings I simply titled Bichos, where I mixed fantasy, animals, and human qualities and interactions in a playful way.

This mode of working proved very fruitful, and in subsequent years I have put together two other solo shows where I explored similar environments and characters but combined them with different research concepts. In 2024, I presented the show Azul, azul, azul as a guest artist at the Ground Floor Contemporary Gallery in Birmingham, Alabama. In this show, I engaged ideas about the provenance and history of the color blue and its psychological associations, and relied on Benjamin Labatut’s essay “Prussian Blue” from his book When We Cease to Understand the World for much of the information and inspiration. Earlier this year, I worked with the amazing team at Institute 193 in Lexington, Kentucky, to bring my solo show titled Tierra adentro/Hinterland to their beautiful space.

In this show, I dug into the history of the interior lands of Argentina, a place of myth and mystery, very different from the capital, Buenos Aires, the center of commerce and the financial hub of the country, through stories by Jorge Luis Borges as well as archival images and documents. The show consisted of drawings, paintings, and sculptures that imagined mythical, eccentric, and beautiful beings occupying and moving freely in this landscape. While the history of the Argentine interior—the pampa in particular—is plagued by violence, starting with the Spanish conquest and continuing into modernity, with the indigenous populations suffering abuse, murder, and displacement, I aimed to create a speculative narrative that did not erase nor contradict reality but expanded it through fantasy and wonder.

MPM: Within this imaginative drama, your depiction of the black cat stands alone. Could you talk about what the cat symbolizes to you, both emotionally and spiritually?

MK: The first painting I made of an anthropomorphized figure is Self-Portrait as a Mother of Pupz. Puppeteer, or Pupz, are some of my cat’s nicknames—his official name is Charlie Korol. He and I are very similar in truly important ways: ways that make up both of our identities, so instead of seeming like a stretch, it seemed appropriate for me to look like him in a painting. He was a street cat, fed and looked after a bit by my neighbors, but in reality he was fending for himself for the first six years of his life. He is a suave, gentlemanly survivor.

When he and I first met on East Hancock Street in Decatur, where I live, we were immediately attracted to each other, and we slowly built our interest into a friendship that grew into a deep love until we became family. The figure of the black cat for me is a symbol of natural intelligence, elegance, beauty, and love; self-assertiveness, independence, survival, and belonging. While the images often reference Charlie Korol, it is not necessarily a portrait of him every time: it can be me, or others who identify with these qualities.

Carolee Schneemann said it best: “I’m blessed with muse-cats who have inspired and guided my work…”. Of course, cats—especially black ones—have many societal stereotypes attached to them, from witches who prefer their company, to the femme-fatale, thieving character of Catwoman, to the “childless cat lady” comment. It is a loaded trope.

MPM: This dark humor seems to play an important role in your paintings. How do you approach the line between humor and unease, and what interests you about that tension?

MK: I think humor is the best way to cope with hardship, but I don’t make art as therapy. I am more interested in it as an intellectual and technical challenge. Some of my favorite artists have a great sense of humor. For example, the Nelly Mae Rowe drawing that reads, “This Kicthing Will Be Close Be Cause of illness, I am sick of cooking.” This is a funny statement, but it is also quite serious when you learn that Rowe worked in domestic service for most of her life before she became an artist.

Humor can carry the lighthearted personality of the artist and create space for hope while addressing serious, difficult topics. It keeps the artwork from becoming heavy-handed and overly explicit, and it allows for the viewer to participate, asking her to put the parts together.

MPM: Your early training was in dance, rather than the visual arts, which led to a professional career before you turned fully to art. How does your background as a dancer manifest visually in these works—particularly in the way bodies move, balance, or interact?

MK: I build my compositions by making each character react to the previous one, using expression and body language to insinuate personalities and actions. I work without any preliminary sketches; the process is reminiscent of a type of dance research, where the choreographer “finds” the movements for the piece by observing the dancers’ motions during extended improvisation sessions. I think my understanding of anatomy and possible body positions comes directly out of my years as a dancer—even though I also spent years doing life drawing, which is my favorite topic to teach to this day.

An important dance teacher of mine once said that one could perform choreography very well, but that doing so did not equal interpreting or truly dancing. Dancing requires freedom and a deep connection to the music and to one’s body—not simply controlling each movement and accurately counting a tempo. In other words, technical skill, control, and virtuosity are not all there is to making art. I think about this a lot when making my work—trying not to make pieces as if each were an exercise, but seeking a freer space where my hand, my eyes, my feelings, and my ideas start to flow in connection. It is much harder to work in this manner, with this expectation, and it brings frustration into the studio, but every now and then I am rewarded when I am able to make a piece that shows that type of freedom.

MPM: Alongside their fluidity, there’s a deliberate awkwardness to your figures, as if they are caught mid-gesture or between poses. How do you use gesture and distortion to convey psychological states or emotional tension?

MK: It is likely also connected to my background in dance, but for me it is important that each piece feels alive, not static. If you observe the real world, you will notice that perfect symmetry is rare, and as we move around a space, our head moves and our attention goes here and there, so eye level and perspective are constantly shifting. Looking is a dynamic act, and I want that sensation present in my images. Even if it is a portrait, I want to feel like there is a possibility for a facial gesture to change in the next moment.

Like many artists, I find beauty in imperfection and in awkwardness because they seem like the most human qualities. I am obsessed with artists like Anna Boghiguian, who can place the viewer in the middle of a scene through her use of composition, scale, line and color, text, and a deep engagement with historical research. Other artists that come to mind, who also use a lot of expressive distortion and humor, are Magdalena Suarez Frimkess, with her funny, intimately scaled sculptures, and the unbelievably great Bill Traylor, with his jaw-dropping compositions of figures, animals, and strange spaces. For me, the more fragile or awkward the form, the more strength and resilience seem to emanate from it. Something silly and awkward can also be deeply serious and moving. It is an interesting contradiction that I lean into in my work.

MPM: Many of your paintings recall illustrated fables. Are there direct literary references to your visual language?

MK: Yes, books and literature are constant sources from which I make my work. I’m not so good at illustrating specific stories, even though now and then I have done that successfully, but I do gather information from reading, and my mind’s eye gets ideas from imagery that comes to me through language. I am lucky to be able to read in three languages: Spanish, Portuguese, and English. Some of my favorite writers who have inspired many of my paintings and drawings include Clarice Lispector, Jorge Luis Borges, Roberto Bolaño, Jean Rhys, Elizabeth Hardwick, and Jane Bowles.

MPM: The paintings feel episodic, almost theatrical. How do you think about storytelling across the series—do you think of them as narrative fragments that might connect into a broader story?

MK: I consider different bodies of work as series, and with each solo show I tend to delve into a specific historical moment, angle, or theme. I also favor specific paper and canvas sizes that I use repeatedly, maybe even obsessively, so there is a bit of a storyboard aesthetic running across it all. Especially with the ink drawings, which are the foundation of my artistic practice, in the sense that if I were sent to a mental institution, I would definitely continue making those, always in that size, 22 x 30 inches.

I want each piece to hold on its own and be interesting to look at alone, without the others around, but it is true that the effect of the work can be incremental, and the more pieces a person sees, the more she starts to make connections across them and ask, “Is this the same character that was doing something else in the previous drawing?” In 2020, I made an artist book to accompany a solo show titled Nightwork, where I was researching the story of the Zwi Migdal in Argentina and Brazil, a mafia ring that trafficked Eastern European women into the region. The book, titled Bataclanas, was the first one where I was telling a somewhat straight story, but the narrative is extremely open-ended and poetic. While each piece in the show stood on its own, I thought that the effect was strongest when seeing all of it together, and that is often the case with each solo show. I feel like when I put together my solo shows, there is an installation aspect that is lost in other contexts, as I often include drawings, paintings, and clay sculptures related to one larger theme.

MPM: This was a wonderful discussion; thank you. Do you have any upcoming shows or projects you’d like to tell us about?

MK: Thank you so much for the thoughtful questions and the opportunity to discuss my work and my life with you so openly. To continue a bit from your previous question about storytelling, this year I continued making artist books as a way to explore narrative and materials differently, and to make art in a format that would be distributed to more people. I have one titled Tango Trap, exploring my artistic influences from back in Buenos Aires, Argentina, to now in Atlanta—the birthplace of trap music—where I have lived for the past ten years.

The original Tango Trap artist book and one of my ink drawings will be shown this coming January at Indigo+Madder Gallery in London, UK, in Keeper, a small group show with a few incredible artists, curated by Maria Owen. We are also going to release Tango Trap in a small edition of about 50 copies through a collaboration with the painter Aineki Traverso, one of the artists in the show Keeper, and her publication Iterance, which highlights painters who write. I am also stoked to participate in a panel discussion titled “Minnie Evans and the Liberatory Power of Dreams” at the High Museum on January 10, 2026, with the curators Katherine Jentleson and María Elena Ortiz. Beyond that, I will have my first solo museum exhibition in the fall of 2026 at the Gadsden Museum of Art in Alabama. I am busy preparing for it all and very excited!

Link to the artists website

Link to the artists Instagram