Heidrun Rathgeb (b. 1967) received her MFA in London at the Slade School of Fine Art, after attending the Byam Shaw School of Art. Solo exhibitions at Haverkampf Leistenschneider (2026); Sea View, Los Angeles, US (2025); Gallery Sofie Van de Velde, Antwerp, BE (2025); and John Martin Gallery, London, UK (2024). Group exhibitions include Bo Lee & Workman Gallery, Bruton, UK (2025); Setareh, Berlin, DE (2025); Gallery Elsa Meunier, Paris, FR (2024); Gallery Sofie Van de Velde, Antwerp, BR (2024); MePaintsMe, New York, NY (2023); the Royal Academy, London, UK (2022, 2023, 2025); Magnus Karlsson Gallery, Sweden (2021 )

MEPAINTSME: Thank you for talking, Heidrun! I’d love to hear a bit about your background. Where did you grow up?

HEIDRUN RATHGEB: I grew up in a small town near Lake Constance in southern Germany, with one brother. I had a relatively carefree childhood. Together with neighboring children, we used to play in the nearby forest, immersed in an abundance of imagination and role-playing. My parents, both scientists and teachers, maintained a strong focus on their professions. I was also raised by my grandmother, a cheerful and loving person who lived with us.

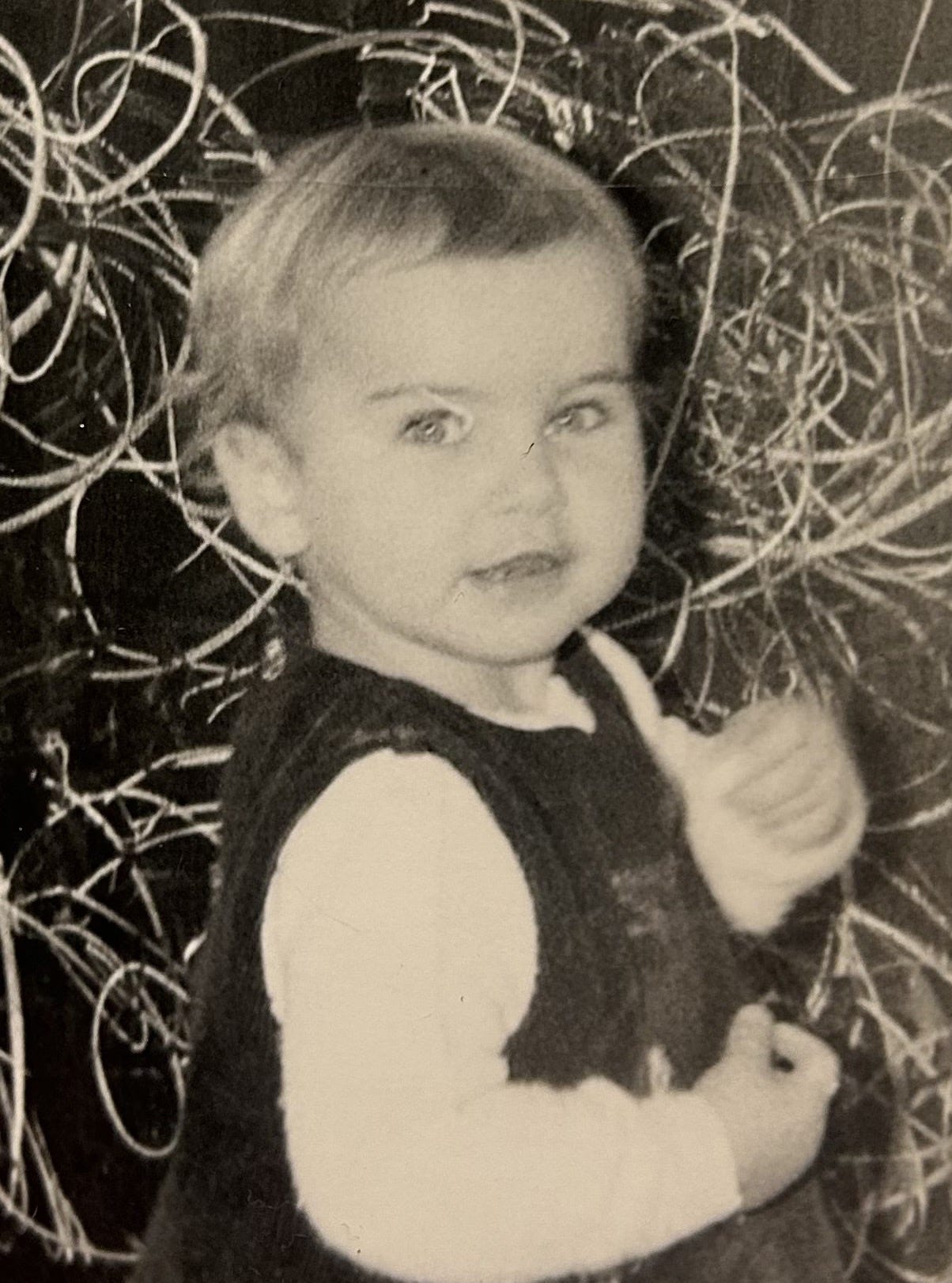

From early childhood, I painted. My mother has told me that from the age of two, I would sometimes paint for eight hours a day, usually with large brushes and watercolor. She kept many of these paintings. There were plenty of art materials around, as my mother had once been an art student herself.

I attended a local primary school and later went to a grammar school, with majors in French, German, and art. In general, I didn’t enjoy school much, as I wanted to spend all my time drawing and painting. Later, after studying zoological illustration in Germany and traveling extensively, I went to art school in London for six years, studying painting first at the Byam Shaw School of Art and then at the Slade School of Fine Art.

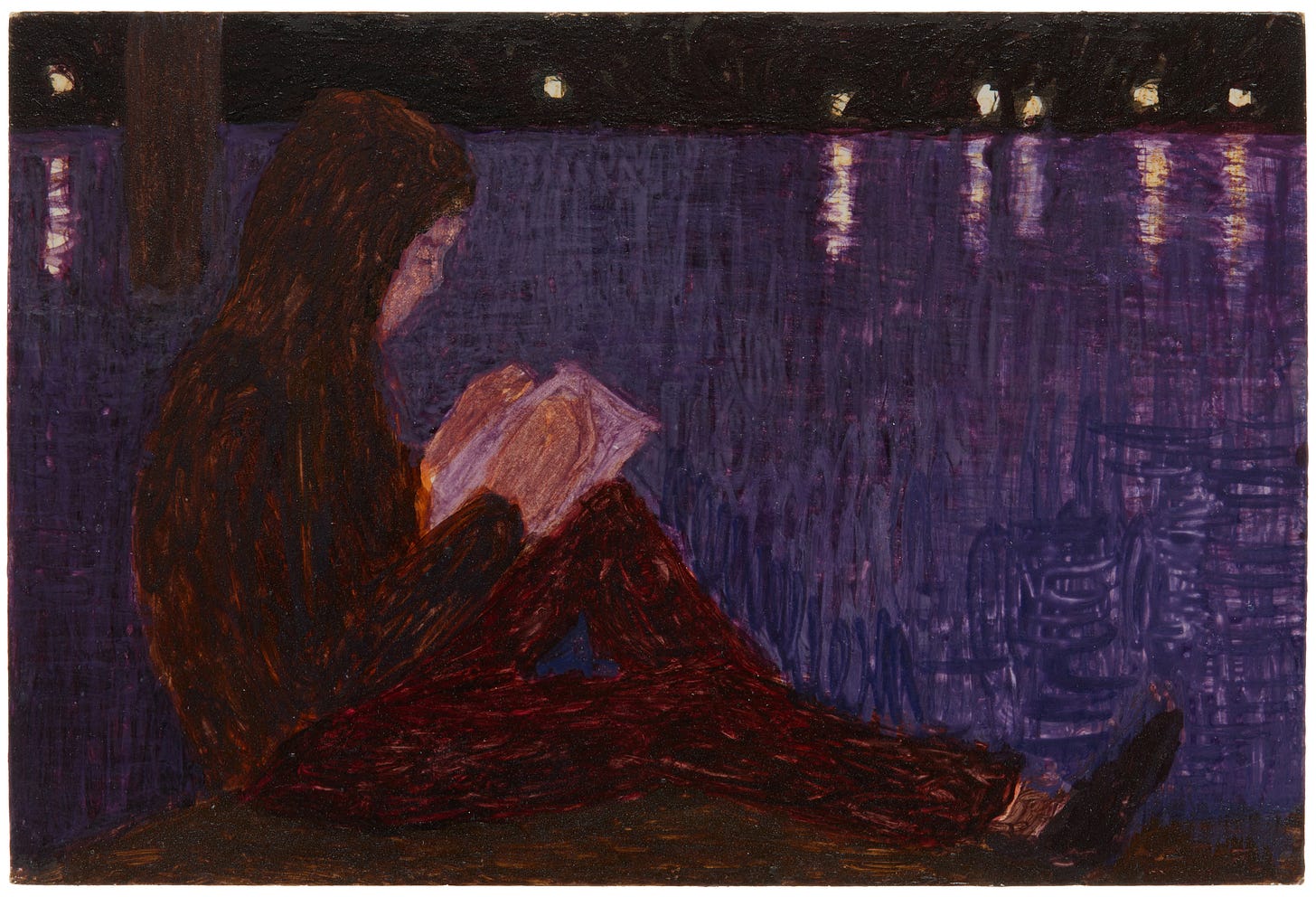

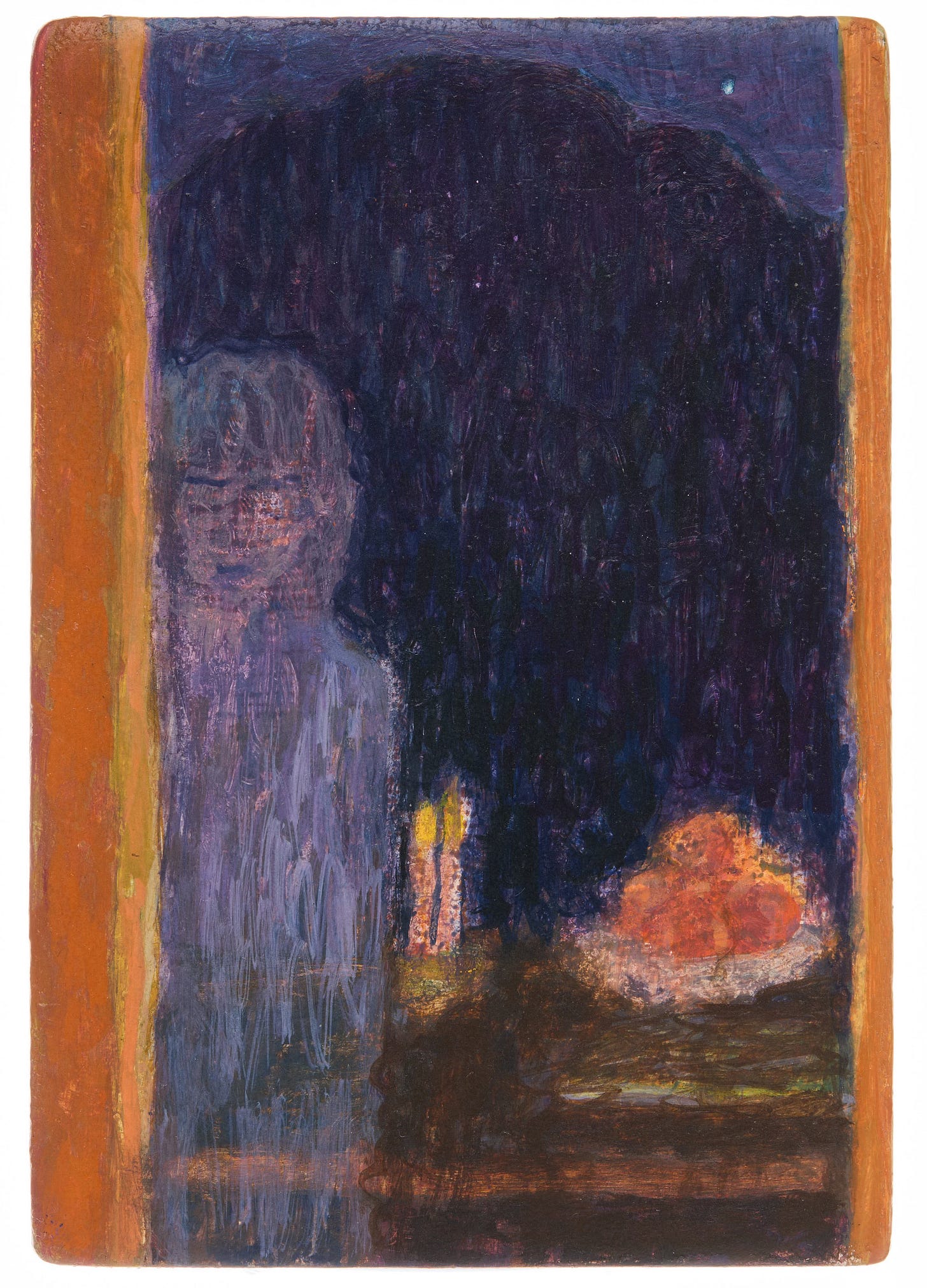

MPM: Your work is most often very small, which I feel amplifies their quiet depiction of intimate life, in the tradition of artists like Bonnard and Vuillard. How do you think scale affects the viewers relationship to the work?

HR: I have always enjoyed working on a small scale. The size of my sketchbooks somehow predicts the scale of my paintings. A friend once said, “Paint as large as you have to and as small as you can.” There are very good reasons for painting large, and for certain subjects it can be absolutely necessary—some things simply don’t work on a small scale. However, my feeling is that today there are many over-scaled paintings, sometimes made for commercial reasons, which I dislike.

Painting small means that every brushstroke counts. It requires a fine balance between color, color transitions, edges, and touch. While I am painting, I hold the panel in my hand. I like the feeling of the heavy panel, the ivory-like gesso, and being physically connected to my paintings. Having the flexibility to turn the painting while working helps me see the abstract patterns.

I also imagine that something of this experience transfers to the viewer: the need to focus, to look closely, and to be drawn into the pictorial realm and its atmosphere.

MPM: Your paintings are made in egg tempera, a medium I’m quite unfamiliar with. What initially drew you to it, and how does it behave differently from most other water-based paints?

HR: When I went to art college, I developed a strong interest in egg tempera due to my love of the Sienese Quattrocento painters. My aim was—and still is—to create luminous and finely tuned color relationships, and egg tempera proves to be a particularly effective medium for that. As a young student, I studied every medieval recipe for egg tempera I could find and spent years experimenting through trial and error.

Today, I sometimes use high-quality egg tempera paints from tubes, but I also make my own using egg yolk, a particular resin, linseed oil, and pigment. Another advantage of egg tempera is that it dries to a satin-matte finish, with a surface that appears somewhere between oil and gouache. Although it is a rather delicate medium to paint with, egg tempera cures over time into a durable, lightfast surface.

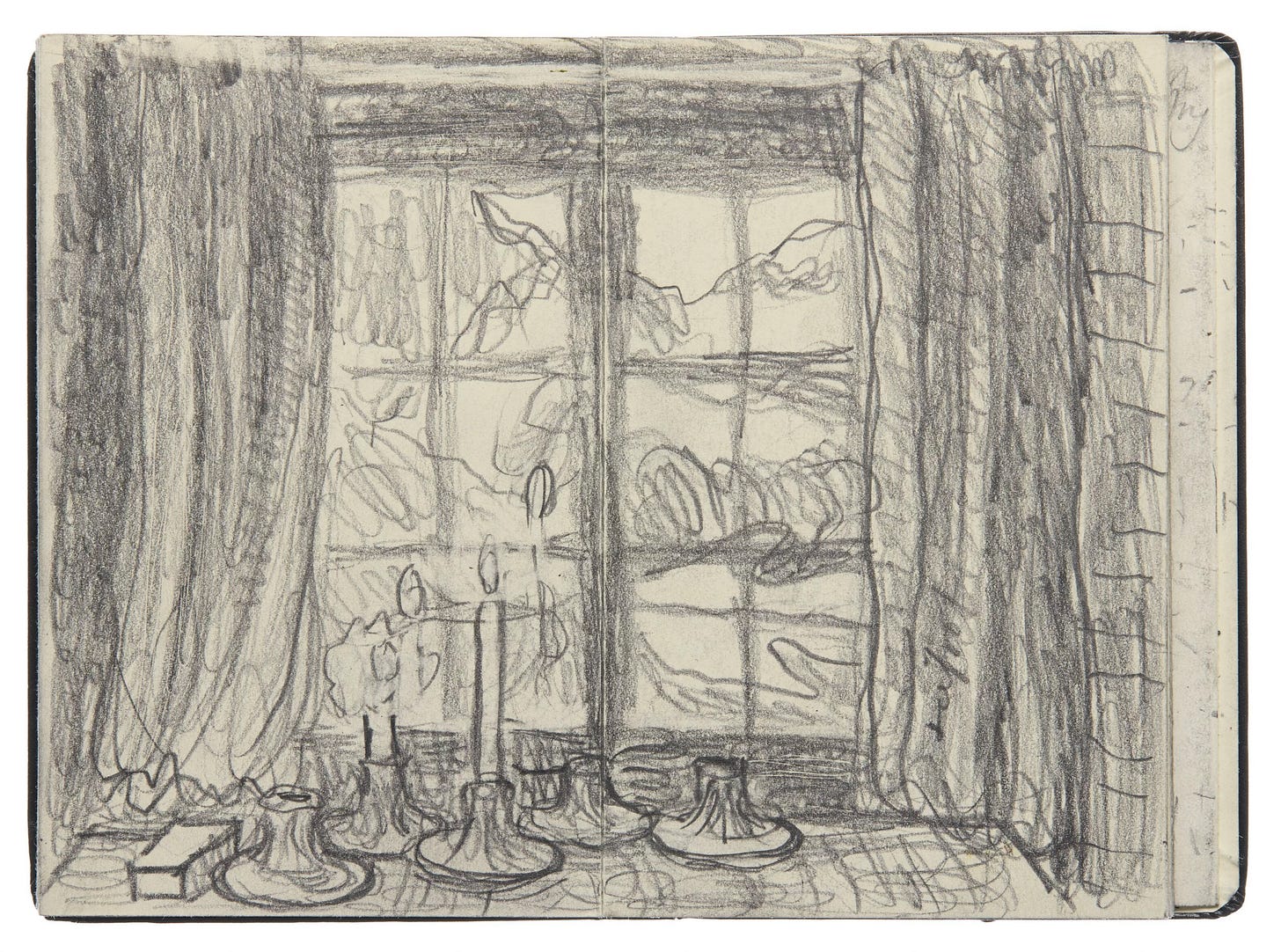

MPM: I’ve read that your painting practice involves a great deal of drawing, mostly from daily life —what you’ve described as “daily epiphanies.” What does drawing allow you to access that other forms of reference cannot? Is capturing the emotional temperature of these moments your primary goal?

HR: Yes, capturing the emotional density of a moment is my core interest in drawing. Although I may look closely at how things relate to one another—this is never random—my drawings are usually made very quickly. I often draw people in specific situations: my children, or someone I feel close to, but I never want them to stay still or pose for me, as that would feel arbitrary or artificial.

For me, drawings hold not only the placement of people and objects in space, but also a multifold memory that I can reaccess even years later when looking through my sketchbooks: memories of scent, wind, temperature, conversation, a particular light, and mood. This is why drawings are, for me, a far richer source for my paintings than a photograph could ever be.

MPM: When you return to a sketch in the studio to begin a painting, color and light are part of the original experience—elements a drawing inevitably loses. Do you make color notations? Is it difficult to recognize when a painting has drifted too far from that initial experience?

HR: Yes, that’s true—a drawing lacks color, but when I look at it, I remember the colors. I love the tension of being a step removed from the original experience; painting directly from perception does not interest me. In my drawings, I sometimes make color notations if there is a particularly exciting color shift or combination, but otherwise I rely on my memory.

Color in a painting does drift away from the original moment, but I don’t mind that at all. In fact, I enjoy creating a parallel color system to the one that exists in the world.

MPM: Do the paintings go through many iterations as you work? How do you know when a painting has reached a sense of completion?

HR: My paintings begin by referring quite accurately to the initial sketch. No matter how rough a drawing is, I always want to take it seriously. After a while, things begin to shift—elements are erased and re-formed. I then put the drawing away, and the painting follows its own path. A painting usually comes to a stop when I feel a balance among all its elements. This is different for each painting.

MPM: Another aspect of your paintings that I love is their physicality. The supports possess a softness—even the corners have a roundness that accentuates their “objectness.” Can you talk about this aspect of the work? How do you prepare your supports?

HR: The materiality of the paints and supports I use is vitally important to me. Inspired by icon paintings, I have always liked working on wood. The sanding and preparation take a long time. I work with traditional gesso, consisting of size and chalk, applied in several thin coats. I regard my paintings as much physical objects as they are flat painted surfaces.

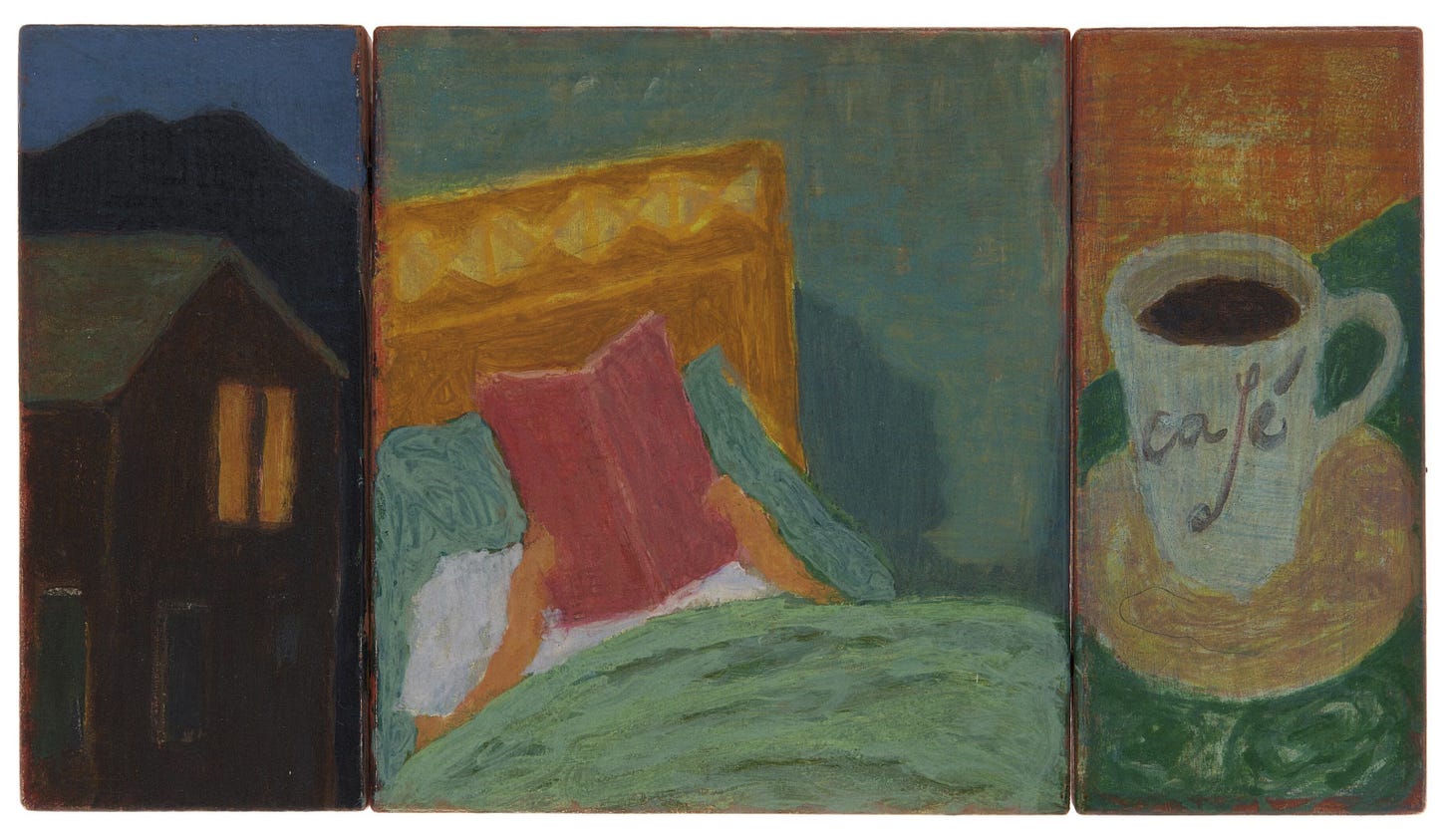

MPM: You exhibited a number of triptychs last year in which each panel represented its own time and place, and I believe the left and right panels could fold inward. How do you think this format was received? Did it operate differently from your single-panel works?

HR: For me, the triptychs are a means of painting a sequence in time. The aspect of time—very specific moments—is important in my work, as opposed to a single panel, which usually refers to just one particular moment. Triptychs allow for a progression: a person moving from one place to the next, an exterior and interior glimpse of a room, and so on. At my exhibition in Antwerp with Gallery Sofie Van de Velde, people seemed to spend a long time looking at the triptychs. Perhaps they function as miniature worlds that viewers can enter. I also see them as a kind of “travel icons,” objects people can take with them when they are on the move.

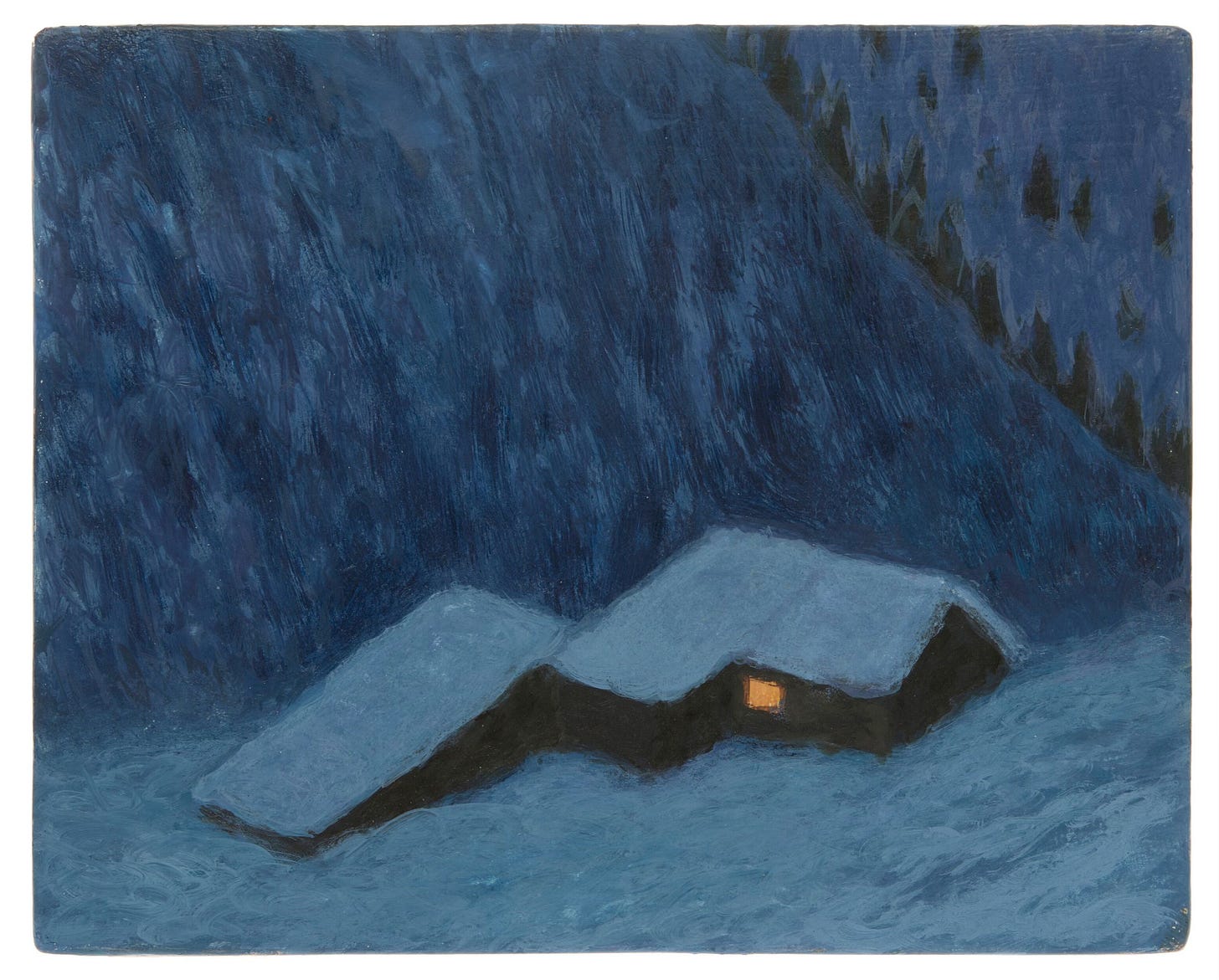

MPM: You return repeatedly to northern countries, to dusk and dawn, and to moonlit nights at home. How do you think about light as both a physical and emotional presence in your paintings?

HR: Yes, I do have an affinity for northern countries, such as Norway or Denmark. Painting moonlit nights has fascinated me for the past 30 years, and I often go out at night to draw. Where I live, there is no light pollution. I think I’m drawn to the luminosity of the moon and to how everything is united by this particular light.

To paint a physical light has been a strong desire of mine since I was an art student. Light is everything in my painting. I am very aware that each painting requires its own specific light, whether it comes from a single source or exists as an overall atmosphere. I want color and light to melt together—perhaps that is what I mean by “physical light.”

MPM: Thank you so much for taking the time to talk. Do you have any current or upcoming exhibitions you’re working on?

HR: At the moment I am exhibiting at Gallery Haverkampf and Leistenschneider in Berlin. My show takes place in the gallery’s Cabinet room, the same space where Katherine Bradford had her first show with the gallery. I am very happy about that. Currently I am working on a publication together with Gallery Sofie van de Velde, Antwerp where I will have my next solo show in Spring 2027.

The way you describe painting small, where every brushstroke counts, really resonates. That physical connection of holding the panel speaks to something thats often lost when scale becomes purely market-driven. What's compelling is how you retain emotional density of sketches years later through multifold memory, which photograps cant replicate. I've been curious about egg tempera's satin-matte finish between oil and gouache, dunno if I'd have patience for delicate application but the luminosity seems worth it.

Beautiful, emotional work. Thank you for sharing