Elliott Green

"I’m thrilled when stuff happens automatically, because it brings naturally convincing results. It seems like it couldn’t have been any other way."

Elliott Green was born in Detroit, Michigan, in 1960. He moved to New York City in 1981 and lived there for twenty-four years. In 2005 he moved to Athens, New York, a small town situated between the Catskill Mountains and the Hudson River, where he continues to work and live. He has received a John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship, two Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grants, the Rome Prize, and three prizes and awards from the Academy of Arts and Letters, along with numerous residency grants. His work is represented by Miles McEnery Gallery.

MEPAINTSME: I’ve been a fan of your work for a long time, but I don’t know much about you. Where did you grow up?

ELLIOTT GREEN: I grew up in the suburbs near Detroit, the fourth in a family of six children.

MPM: Wow! Were you always doing art from a young age?

EG: In the early 1970’s, the profoundly talented painter, Brenda Goodman, who is now quite well-known, was my father’s patient, and in exchange for dental services (my Father was a dentist) she gave art lessons to me and my siblings at the kitchen table. I remember her showing us a book by Dubuffet to point out the virtues of his naive visual language. In my teens, I spent a lot of time on the potter’s wheel, and I liked to look at art books. At 16, I aspired to be a playwright or a novelist, so I read fervently and often.

MPM: Did you study painting in college? Where did you go to school?

When I was a sophomore at the University of Michigan, I began drawing heads in the margins of my lecture notebooks. The drawings got steadily better and overpassed the writing. I signed up for a class on German Expressionism that further excited my passion: I shifted my academic focus from literature to art history.

MPM: Interesting. Was that a difficult transition?

Rudolph Arnheim was an esteemed professor in Ann Arbor and his lectures were extremely practical, which appealed to me. He analyzed art from the perspective of psychology, and he had been friends with Freud and Picasso, among many others. Arnheim wrote Art and Visual Perception, which is a valuable guide for making and appreciating all manners of art. It was helpful for me to know how shapes and compositions can be optimally formed and positioned to both transmit and to evoke stronger feelings and clearer ideas.

I had been obsessed with metaphors and analogies in written language, and it seemed it was possible I could use picture-making to cut to the chase. Carl Jung’s Man and His Symbols has also been an important book for me.

MPM: You came to New York around 1981 correct? Had you already decided to pursue painting at this time?

EG: In the spring of 1981, after three years of college, I dropped out and went to live in New York City to be nearer to the major museums and contemporary galleries, and to learn how to paint. My parents were very helpful and encouraging, so that made it less of a leap into the void. I signed up for a figure drawing class at the Art Students League. But that didn’t last long. Not much later, I noticed a bulletin board listing for a job as an art restorer’s assistant. I inquired and was hired, and that’s where I learned the basics about the materials and practices of oil painting. I worked at that studio for about a year. We cleaned and repaired decorative 19th century landscape paintings. And from that time on, I painted alone at home.

MPM: I remember first seeing your work in the early 90’s and how much it stood apart from other painters from that period. In an era dominated by postmodernism and Neo-conceptualism, what was the general reaction to those early figurative paintings?

EG: My work did look different, and for some people it was exciting. I think seeing it shown in Soho heartened certain painters to use more imagination and intuition in their paintings.

I was given encouragement and felt appreciation from collectors and like- minded artists. Joe Fawbush showed my work—he was a great person, friend, and advocate; and later in the decade after Joe died, Magda Sawon from Postmasters respectfully presented my work.

There were other artists who were making idiosyncratic paintings too, and Outsider art was gaining a larger audience. At Hirschl & Adler Modern, where I showed in 1989 and 1991, I was exposed to the wonderful outliers Bill Traylor and Forrest Bess for the first time, so I knew that degree of individuation was possible.

MPM: Could you speak to what drew you to that particular aesthetic and conceptual approach early on? What were you exploring with that strange mix of abstraction and gestural caricature?

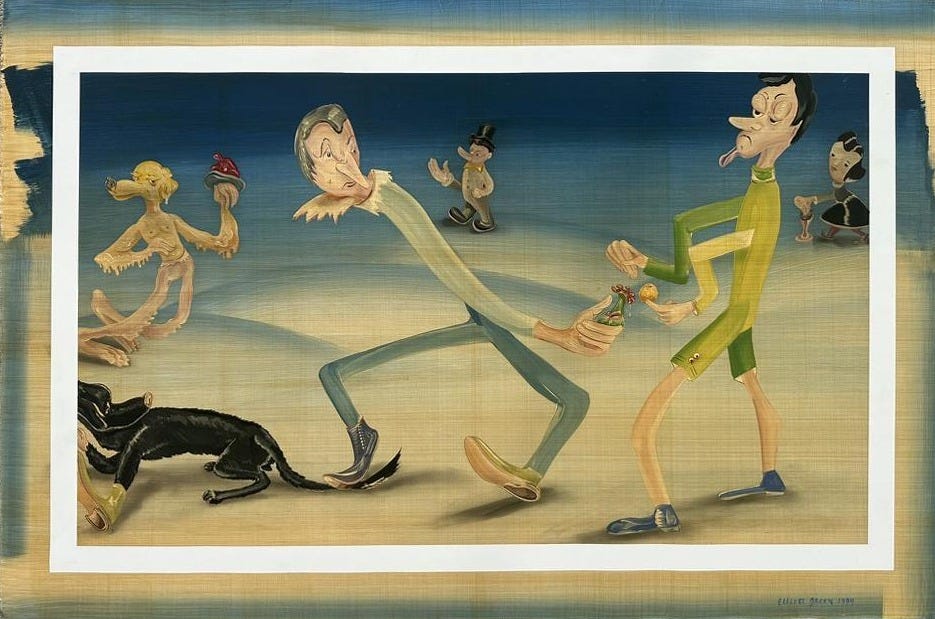

EG: From the very start, I sought aliveness, freshness, and accessibility, which is what I admired in my favorite illustrations, cartoons, and caricatures. Dr. Seuss for one. Daumier, Steig, Hirschfeld, and Covarrubias all produced incredibly articulate drawings.

But alternatively, I hoped to use that expressive and imaginative language to pursue and represent original ideas sourced from the depths of my subconscious. I was reaching into my psyche for buried truth and some of what surfaced embarrassed me; but I was determined to accept whatever came to mind. I thought, if what arises is totally disgusting, I’ll still follow it through and then keep it hidden in a drawer forever. Thirty years later, it’s still eccentric, but it doesn’t seem disturbing to me.

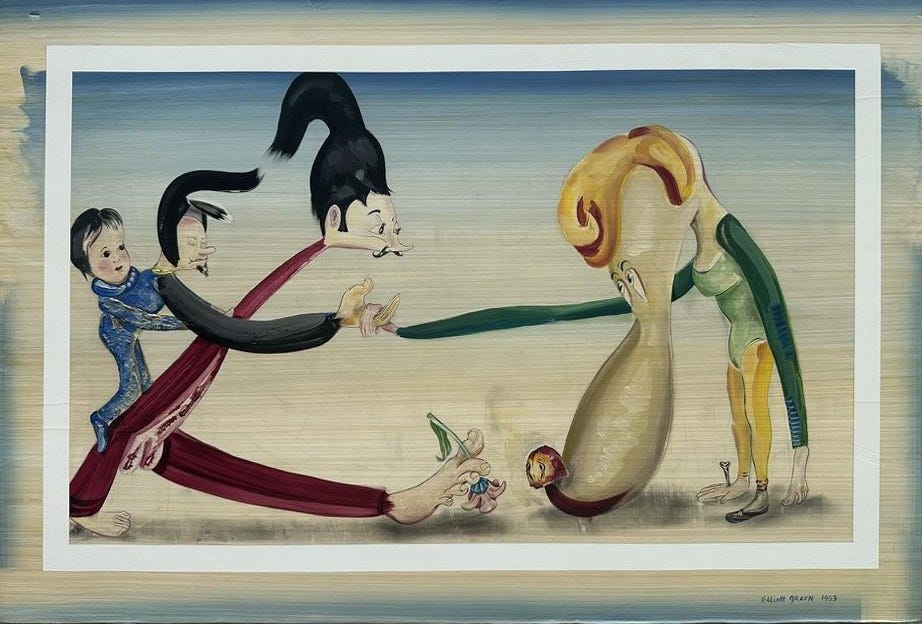

There were sexual references that were more metaphorical than erotic. Themes of innocence, vulnerability and a desire for connection were enacted with abstraction and absurdity. I was afraid that if I sanitized my pure imagination, it would stop flowing, and I loved having it. If what emerged surprised me and made me laugh—that was a sure sign that I hit a nerve. A high-speed painterly gesture is a quick and effective way to evoke an ejaculatory catharsis.

The Emergences was a series I worked on from 1992 to 1994. I began each of those paintings with improvised penciling that I later filled in with acrylic paint. I appreciated the virtues of both imagery and abstraction and saw how they could be combined to make something new and different. I remember describing my work to someone as, tragedy performed with the stage lighting of a musical comedy, and they said, that doesn’t sound like a good idea.

MPM: What prompted your shift from figurative works to the abstract landscapes you’re known for today?

EG: In 2005, two life-changing shifts occurred. My parents, who I adored, had died a year and a half apart after long illnesses. During that mournful period, I was in a rut. I had been laboring on my “Crowd Drawings”. They were jammed to capacity with entangled bodies and heads. It seemed like they contained everyone I had ever met at a glance and summed up my life in review. I remember doing several of these drawings on a clipboard while keeping my father company in his hospital room.

Later that year, I left the city and bought a house in Athens, New York, with a large, heated garage that makes an ideal painting studio. It quadrupled my workspace.In the country, with pressures lifted, my compositions opened up again. The figures were broken down into elementary anatomical parts. An intestinal motif that looked like both brains and guts was a component that kept coming up; kidney, stomach, and bone shapes appeared, too. The organs were dispersed, then reattached with free-form connections. When it was finally time to scale up, I used pointed brushes and graphite oil paint on linen, which was a perfect substitution for the pencil. The looseness was liberating. Pockets of sky blue appeared, and it was like doors opened up and filled all the spaces with fresh springtime breezes. I was a Fellow at the American Academy in Rome in 2012 when the first landscape surfaced. Mountains, valleys, lakes, and temperamental skies came into the paintings when I had been inspired by the soul lifting effects of expansive vistas.

A spatial depth unfurled when the compressed layers of personified abstraction were teased apart and placed from back to front in increasing scale. They became landmarks in a landscape space, and a blue gradient descending from the top added a far-reaching area for skies and an assortment of weathers.

MPM: Your landscapes are built by what I see as an almost cinematic sense of movement, gestures that are constantly building and collapsing leaving a residue of decisions. Do you see this simultaneous form of creation and destruction akin to nature?

The discovery of plate tectonics changes the mind-frame of landscape forever. The rise and fall of mountains, civilizations, and lifespans are all eventualities of nature that I try to comprehend with a visceral fullness.

When I was a college student, I saw this Picasso drawing that I’ve never forgotten. You can see the erasures where the horse’s legs had been before the artist replaced them with better ones. That instance of transparency infuses living action and spirit into the picture’s subject. Ever since, whenever appropriate, I leave a trace of the decisions, corrections, and revisions in my work to reveal origin, the searching and the soul-making of experience.

To truly expose the trail of how it happens in my pictures, I made actual animations in 1999. These were drawn on clear Lexan film taped to a digital scanner. Draw, scan, draw, scan, etc. The final images called, Sketch Movie Stills, were compiled into a portfolio of photo-lithographs at Columbia University’s Center for Print Studies. I was at it again in 2014, when I elevated a camera over my desk and photographed 12 x 16-inch oil paintings progressing at intervals. They became the basis for a collaboration called, Creation Stories, with my friend Colin Gee, who is a videographer, producer and performer. He added his gesturing hands and a soundtrack to the developing footage.

My paint rags replay the creation and destruction narrative you mentioned, when they wipe away whole sections of the scenery like devastating floods and avalanches. As a matter of course those eradicated passages get refilled with the next shift of regenerative growth.

People familiar with my earlier characters are amused to see how the landforms in my later paintings strike recognizable poses and attitudes. They tend to lean into each other hoping for attachment or seem to be parading in the direction of an alluring distant destination.

MPM: I think of Max Ernst and how he created organic forms through these material techniques. Do you feel responding to paint’s randomness leads to a deeper sense of naturalism than simply depicting landscape?

EG: I’m thrilled when stuff happens automatically, because it brings naturally convincing results. It seems like it couldn’t have been any other way. That’s not to say that finding fluency didn’t take me years of practice. Many of the phantom erasures in The Emergences were awkward lines redrawn again and again until their trajectories were just right. When I’m in a relaxed exploratory state, feeling bodiless and selfless, things emerge spontaneously. Some property of paint, arriving in shorthand, resembles a landmark or a fossil or a waterfall or an insect. I watch for these arrivals and try to provide a meaningful context to surround them that doesn’t interfere with their sincerity.

MPM: I’ve seen a real development in the variety of your application of paint in your landscapes. What types of tools do you use to create such variety?

EG: I use sponges and foams cut into various shapes. I use rollers, windshield wipers, and taping knives. I have rubber-toothed combs. I use my fingers, fleece, and microfiber rags. I use taklon brushes, sometimes bound into bunches. How I hold the tools with specialized handles changes the voice of a marking. I’ll be demonstrating my methods in more soon to be released videos made with Colin.1.

MPM: Do you also see your landscapes as psychological spaces?

EG: Every painting is a metaphor for what it feels like to inhabit a body and a mind on earth. There’s elation, depression, love, desire, shame, disappointment, anger, noise, quiet, compassion, sympathy, fever and chills, and whatever else I’m forgetting from the cadre of emotions embedded in the scenery. Those feelings are in the posture of the mountains and the body languages of clouds and rivers. Some of my early landscapes were named after mapped areas of the brain. My title, North of the Hippocampus, refers to the entorhinal cortex, which is where the neurons for navigation and orientation are located.

MPM: Some of your recent paintings on plywood have a sereneness to them. They feel more an exploration of light as opposed to terrain. Can you talk about this group?

EG: Yes, I think you are right—it’s a new direction. The central focus of these paintings is their luminous energy. For one thing, there’s no graphite on them, which lightens the tonal gravity. Nurser is interesting because the foreground figure materializes from out of the blue light at the sides. The metaphysical atmosphere at the top reaches around to embrace the subject matter in front.The plywood boards were used on rolling racks that came from a shuttered bagel factory. I bought them for storage, but one day I saw their appeal as a substrate. They have distress marks, and it seems poignant to contrast that rough-and-tumble history with the charismatic radiance and grace of aura effects.

MPM: Well, I’m very excited to be including a work from this series, as well as an example of some of your earlier work in MPM / IRL. Do you have any other shows or projects coming up that you’d like to mention?

EG: Thank you! I appreciate your thoughtful questions: it’s been fun to remember old work and past times again. And thank you for including me in MPM/IRL with this fine group of artists. And thanks also for all the meaningful images you’ve brought for us over the years. You’re a superb Curator and Soul-finder. Your selection of artworks and artifacts are always genuine, sublime, beautiful, and profoundly engaging.

I’m preparing for my third one-person show at the Miles McEnery Gallery, which is scheduled for 2026.

Elliot Green’s paintings are currently on view in the MEPAINTSME group exhibition MPM / IRL, on view at 48 Hester Street, NYC, from July 11 - 27, 2025.

The artist is represented by Miles McEnery Gallery, New York.

Wow! Beautiful and a true painter’s painter. The work is amazing and the craftsmanship and wide use of materials is interesting. I’d like to see these paintings in person. I’ll bookmark this interview.