David Surman

"Painting ideas have their own agenda and come out how they want to be."

David Surman (b. 1981) is an artist based in London. He studied animation film at Newport Film School (2002) and film studies at the University of Warwick (2004). Working primarily in painting and drawing, he has established an international reputation for his figurative works that feature striking kinetic compositions of animal, plant and human forms. Surman's work celebrates the vitality of its subjects and painting as a medium. Recent solo exhibitions include: Sleepless Moon, THEO, Seoul (2024) ; Portraits of a Wild Family, SENS Gallery, Hong Kong (2022); Carousel, Tinimini Room, Dordrecht (2022); Fairy Painting, Sim Smith, London (2021).

MEPAINTSME: For those unfamiliar with your work, how would you best describe your paintings?

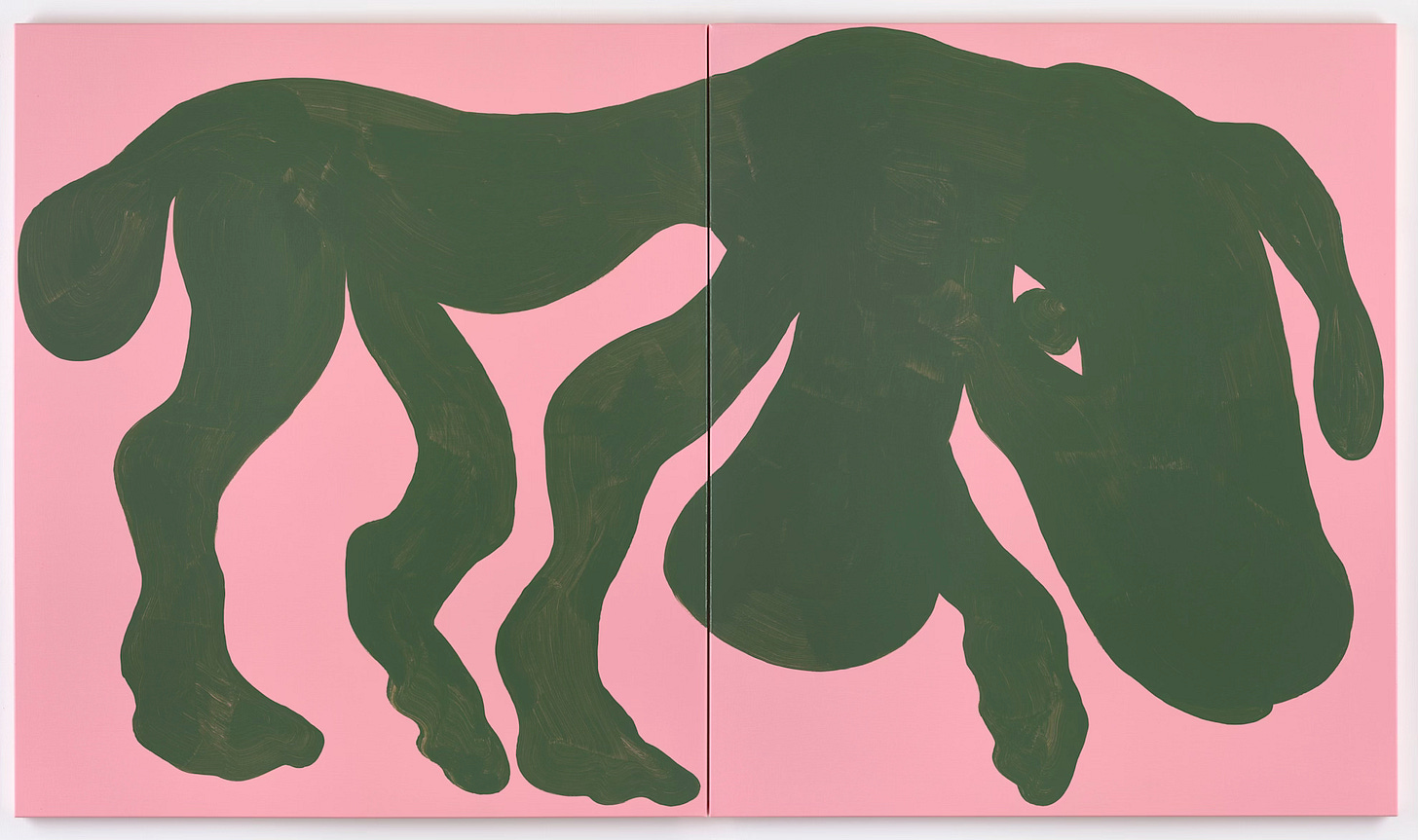

DAVID SURMAN: I have been making figurative paintings, primarily of animals for the last eight years or so. I like to hang different ideas onto the animal body, which has a kind of universality and invites people in. Sometimes the paintings are barely holding together formally, other times they come up to the threshold of orderliness. Sometimes there is a landscape, a sense of place, cut through with a feeling. Almost everything sits on the foremost plane, flirting with abstraction. Though my work is not overtly political, I do think there’s a question running through it all about what we choose to look at and value. I’m interested in making work that visualises and invents and provokes around a familiar figurative world. I try to make paintings that are multidimensional, and I can only speak for myself, but there’s an easy aspect and an implacable aspect. I’m trying to refresh my heart and my eyes with each painting.

MPM: I’d love to hear a bit about your background, where did you grow up?

DS: I come from a big family — my mum was a housewife with untapped artistic talent and my dad was an outdoorsy guy. I grew up in the rural southwest England and then moved to northwest Scotland, and the thing about these places is that they’re stunningly beautiful, and at the same time economically deprived. There’s a kind of downtrodden farmyard of domesticated animals in my work that encapsulates the memories of this world. It’s the same story in many places around the globe, beauty and desperation, and in the 80s and 90s the sense of isolation was deeper because of the lack of internet culture. I had a breakthrough during my early childhood -- drawing gave me some precious currency that assuaged loneliness and drew people to me. So very early on the mode of communication became art, and then later enthusiasm for film and media. My parents didn’t know how to guide me but they had the wisdom to push me toward an artist who lived nearby called Robert Fairley, a tremendous influence. He showed me painting, but also a lot of experimental performance and film work on VHS. From Franco B to Sadie Benning to Viennese Actionism, full beam. He wanted to provoke me and activate my mind, it was the foundation. Age 16 or so I decided I wanted to do film rather than painting, because the possibilities seemed larger. At the same time I was a closeted gay kid and the pressure-cooker of those feelings meant I had to get out of the rural world, and so I left school early and kicked around for a bit, and eventually got to film school.

MPM: I’ve read that you had that early interest in animation and eventually studied it in school. I was a self taught animator in my young years and this piqued my curiosity. Can you talk a bit about animation and filmmaking?

DS: In the late 90s there was a really great undergraduate film school in this declining industrial city in Wales called Newport. It had incredible people coming through the doors like Martin Parr, Richard Billingham, Peter Greenaway and Ken Russell, it was a diamond in the rough. They closed the school after the 2008 crash because they had investments in Icelandic banks. There had been a really active independent film scene in the 90s in the UK driven by broadcasters, including incredible animators. The Brothers Quay, Joanna Quinn who was a teacher of mine, real visionaries. I was inspired by that scene but also by the animation coming out of Japan. I started making traditional hand drawn animation and quickly acclimated to that world, but then I wanted to fuck things up and experiment more, using cut-up and collage processes and new digital cameras to work much more directly with the image. I realised early on I wanted to get to certain sensations and intensity through formal means, editing, structure, even if the image wasn’t provocative in its subject. Robert Breer and Chris Marker were a big influence on me through postgraduate film, too. Doing new things with the familiar is something I took from them.

MPM: So how did you eventually find your way into painting?

DS: My painting was always happening intermittently in the background, but at the time in the early 2000s it was easier and more vital to project a huge moving image than make a big painting. Eventually, there came a point around 2014 when I got curious again about the possibility of making a painting with all the accumulated experience I had built up from film and animation and video games. The internet did weird things to film that it’s now doing to painting. Paintings have a silence, and objective presence, that I got excited about again.

MPM: Drawing seems to be an immense part of your practice?

DS: In everything I’ve done I’m always drawing. I’ve really been drawing non stop since 1997 or so and everything good comes out of that accumulation, and it’s the reason line is such a feature of my work too. In my current works I’m plagiarising my own kid drawing from the early 80s.

MPM: Now you live and work in London, correct? Do you live separately from your studio? Is having a separate live/work relationship important to you?

DS: I’m very lucky as I live ten minutes away from my studio in a neighbourhood called Deptford in southeast London. I live with my partner, Ian Gouldstone, who is also an artist. The studio is where I spend most of my waking time. Painting is an activity that demands long periods of solitude and it places unexpected emotional pressures on you if you don’t attend to it regularly. If I take a long period away from the studio and stop making work I start to feel physically out of sorts. Doing something there each day keeps the pulse beating. With the exception of Sundays. Sundays are for rest.

MPM: What’s a typical day like (schedule wise) for you in the studio?

DS: I wake up and do anything that needs a computer until midday. I go out for lunch somewhere close to the studio and then from around 1:30pm I’m there until around 7-8pm. Then I go home and eat, and sleep at around midnight. During my time at the studio I will have spent a long time looking. Really that's the biggest thing. I will look at blank or imprimatura canvases for hours, and also the completed work too. Being an artist is permission to look first and foremost, to even stare -- the obligation to make something is secondary. I paint quickly and decisively, based on a slow process of looking and waiting for the idea to alight on my thoughts. I like the feeling that a painting ‘arrives’ and then my job is to report that event onto the canvas, it’s an urgent quick sort of thing surrounded by lots of waiting.

MPM: Your compositions often hold a singular creature within a flat space, however your approach to each work varies -- some are very direct, simple and flat, while other works are precise silhouettes; some manifest with a half dozen strokes while others are more fleshed out. Are these conscious choices to explore variables in a painting? Do size and materials play a role?

DS: Painting ideas have their own agenda and come out how they want to be. I try not to censor a painting idea because it doesn’t fit an arbitrary notion of what constitutes ‘my’ work. It’s all my work because I’m doing it. Repetition in art is only useful insofar as it insistently sets out a project, and you could say I’ve done that with my focus on animal figures, but the painting method is completely free. I’m emphatically a fan of the line of a leg, a back, an eye, an ear. I like the composition of the ‘circle within the square’, that is something central pushing out at the boundaries of the work, drawing attention to them and overcoming them. I find painting that is indebted to photography generally less interesting because of how the lens impacts the relation to the edges. I work from memory, imagination and invention because then I feel free to find some new sensation of activation without needing to serve some exterior point of reference. I try not to overload my work, no one painting has to do everything.

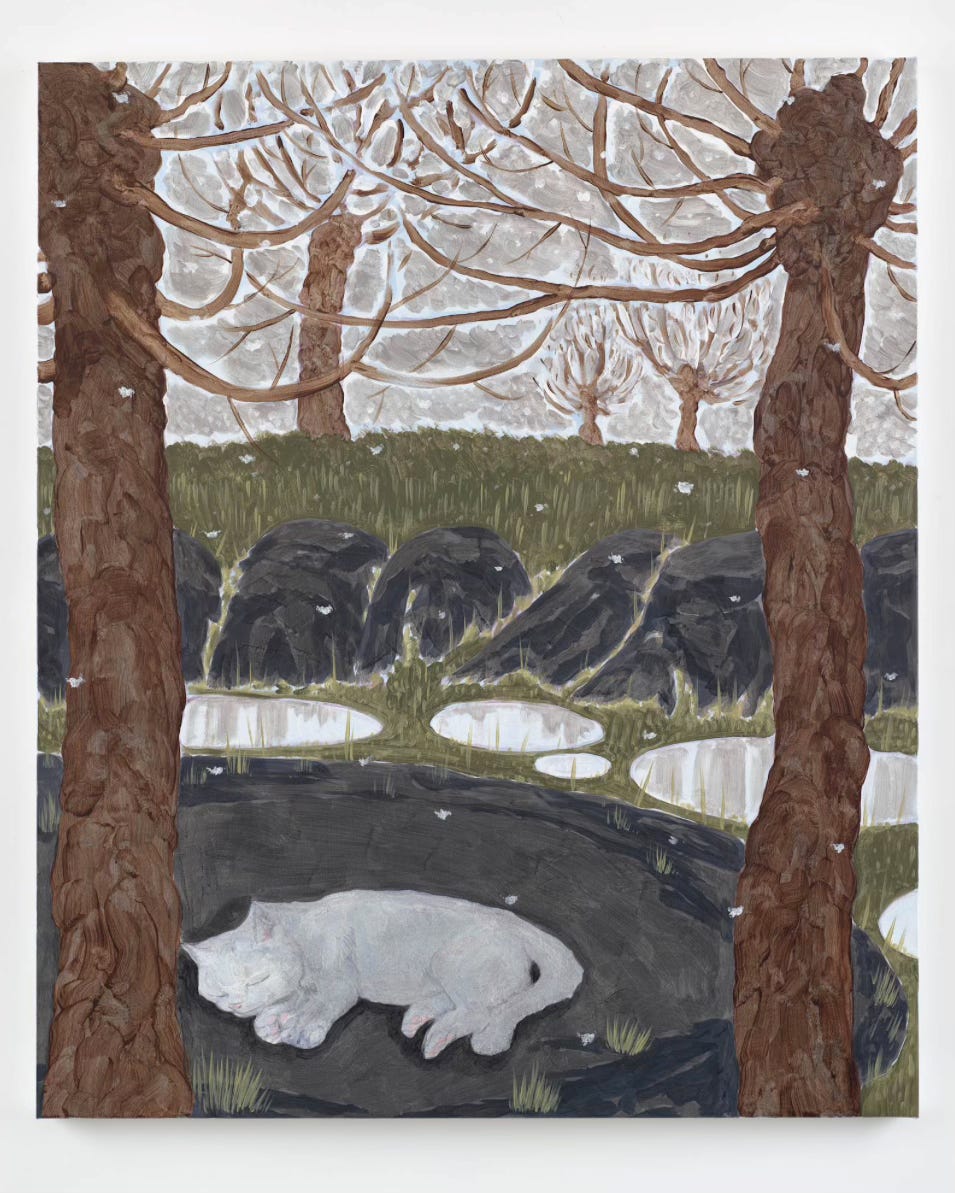

MPM: In your exhibition titled Sleepless Moon at THEO Gallery, the landscape and how the animals interact with nature has entered into the work. This feels like a very natural evolution, but could you talk a bit about this development?

DS: I started those paintings in the autumn of 2023, and on my birthday in October, the dreadful conflict in the middle east erupted. The spectacle of human suffering made me acutely conscious of notions of place, territory and belonging. These thoughts and the 24/7 media were constantly in the background of my mind. Going into the studio it felt somehow inappropriate to make pictures with the same aggressive attacking gesture and sense of placeless abstraction. I found myself going back in my mind to the Highlands of Scotland, a home place I knew well. The paintings have a stillness with less emphasis on movement, and so the gestures shrank and the forms became more distinct. For me, the show had to do with a sense of fatigue in the world from consecutive disasters, and I intended the work to point to a quiet way through that without any triumphalism. The gallery team at THEO were supportive even though it was such a departure. It was a romantic figure-landscape show about a kind of slow peaceful time, made in opposition to the ever-present time of digitized life into which a war was being folded.

MPM: If we're lucky enough to encounter nature it's very often fleeting, so the directness and fluidity of your brushwork embodies your subjects beautifully. To achieve this do you generally work a painting in one sitting? Can you talk a bit about how a painting develops?

DS: I spend a long time looking at the canvas, and if that works then I will draw directly with charcoal to rough out the forms that come to mind. Sometimes to move things along a bit I will apply a colour imprimatura and then draw into it with the brush after a period of looking. Then I will mix colour for a long time to try and get to something that serves the idea. But really what are painting ideas? They’re somewhere below a clear conception, so the drawing isn’t really it, and the colour isn’t really it. So you get frustrated and then you have to attack it with a burst of painting and hopefully get to a point of clarity and completion in one go. That’s my approach. One session of painting most of the time, two if the work is really big. A successful painting has a feeling of presence in the figure that reverberates through the paint. I think all figurative painting is on a spectrum somewhere between analytic and devotional, and my work definitely swings toward the devotional.

MPM: Have you encountered a dismissive attitude toward wildlife as a subject? Why do you think your work transcends this type of criticism?

DS: There’s a definite sense of dismissiveness around paintings of animals that has a social class dimension, because so often it is the work of children, amateurs and for popular consumption. It is as if the animal is an inadequately complex subject, too shallow, too simple in its emotional and intellectual register. This whole negative baggage thing is a motivator for me, because it suggests to me that there is untapped psychic potential in it. For the same reason I will use the language of cuteness and modernism interchangeably when painting animals because it rubs up against the bounded social nature of taste. But I would add that the default mode in art cultural appreciation today is dismissive, because of the sheer volume of output delivered to us via screens, and we can also observe how art enthusiasm has become a weird kind of caricature of surplus enjoyment in its own right. We’re living in incredibly strange times, and that gives me the conviction to carry on with this project of painting the animal.

MPM: Aside from your show at Theo Gallery do you have any other shows or projects you’d like to mention?

DS: I’m currently working on paintings for a solo show opening this coming March 2025 at Rebecca Hossack Gallery in London. The show is called Divas Everywhere and it’s a devotional show of new animal works. After a few years of painting in acrylic it’s also a return to working in oil, and I’ve been really enjoying that. After that, Ian Gouldstone and I have a two-person show opening in September 2025 in New Orleans at Sibyl Gallery that is going to be special. In a couple of weeks I have work in a group show celebrating the anniversary of Haricot Gallery here in London.

Loved this interview… “It’s the same story in many places around the globe, beauty and desperation” … 🤍