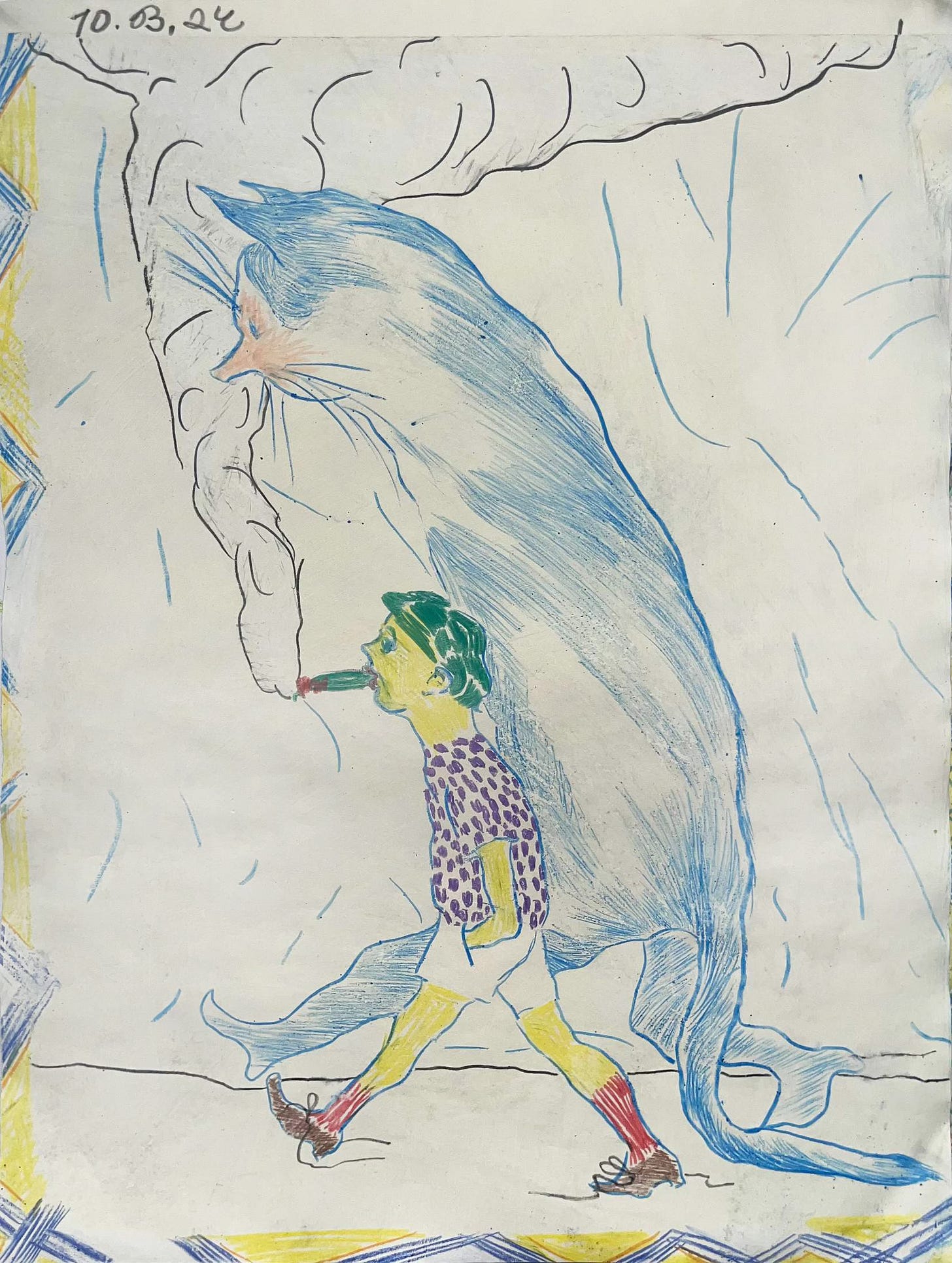

Dasha Shishkin

"The ideas of 'what if' and 'why not' are the driving forces. I am living vicariously through drawing."

Dasha Shishkin (born 1977) earned a BFA from the New School for Social Research, 2001, and an MFA from Columbia University in 2006. She has had solo exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Santa Barbara, CA; the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH; and the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art, Boulder, CO. Group exhibitions include “Greater New York,” MoMA PS1, New York; Saatchi Gallery, London; and the Dakis Joannou Collection, Athens. Work in public collections includes: the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, Pinakothek der Moderne, Cincinnati Art Museum, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Hamburger Kunsthalle, the Art Institute of Chicago, Neues Museum Nürnberg, Museum of Old and New Art, and the Cleveland Museum of Art.

MEPAINTSME: I really don’t know anything about you other than your work. Could you talk a bit about where you grew up?

DASHA SHISHKIN: I was born in Moscow, Russia, and moved to the US with my family when I was 15.

MPM: Were there any important people or experiences that led you to becoming a professional artist?

DS: I think it would be important to define “professional artist” as a term. One that arts for a livelihood, maybe?

I always drew and made up things, like any kid, so not too much weight on that. I did not think of that as a profession.

When the first gallery I worked with, Grimm/Rosenfeld, began to show and sell my work, that is when “professionalism” entered my mind and lexicon, perhaps. The disciplined approach to making drawings, sense of responsibility to the work, to some extent, etc. It was an important formative relationship.

MPM: When I first encountered your work, what immediately struck me was that your large ‘serious’ works had the same level of focus and directness as a casual sketch or doodle. Canvases that might be seen as poorly cut or extraneous to some artists were as relevant to you as beautifully stretched linen canvases. Can you talk a little about your approach to your work and your choices of support/materials?

DS: There are underdogs in the art-materials’ world and I feel for them. Maybe it is a self-deprecating moment in the whole process, or maybe it is just the guilt of claiming something brand new and “perfect” for the selfish act of drawing.

Certainly, there are times when I start or, have some reason to start, with a pristine support or a specific tool, but more often than not I go through the materials already in the studio and choose a size first, then it usually leads to reacting to the surface, etc. and the image grows out of that reaction.

I don’t make sketches in advance and proceed to figuring the images out on the “final” surface. And since I don’t exactly know where I am going in the beginning of the process, it doesn't really matter where I start, therefore the materials are part of that whole thing and they don’t have to answer to any standard either. It's a free for all.

I do feel that a doodle is as important as a “serious” composition and consciously strive to avoid the hierarchy in the studio. The economy of means that is a doodle is magnificent and is my ultimate goal (in some ways achievable through materials as well).

MPM: Talking about your work, there is an eroticism to your subjects that feels centered around sensory delights, oral pleasures. Your subjects seem to relish their hedonism. Can you talk a bit about these types of ideas in your work?

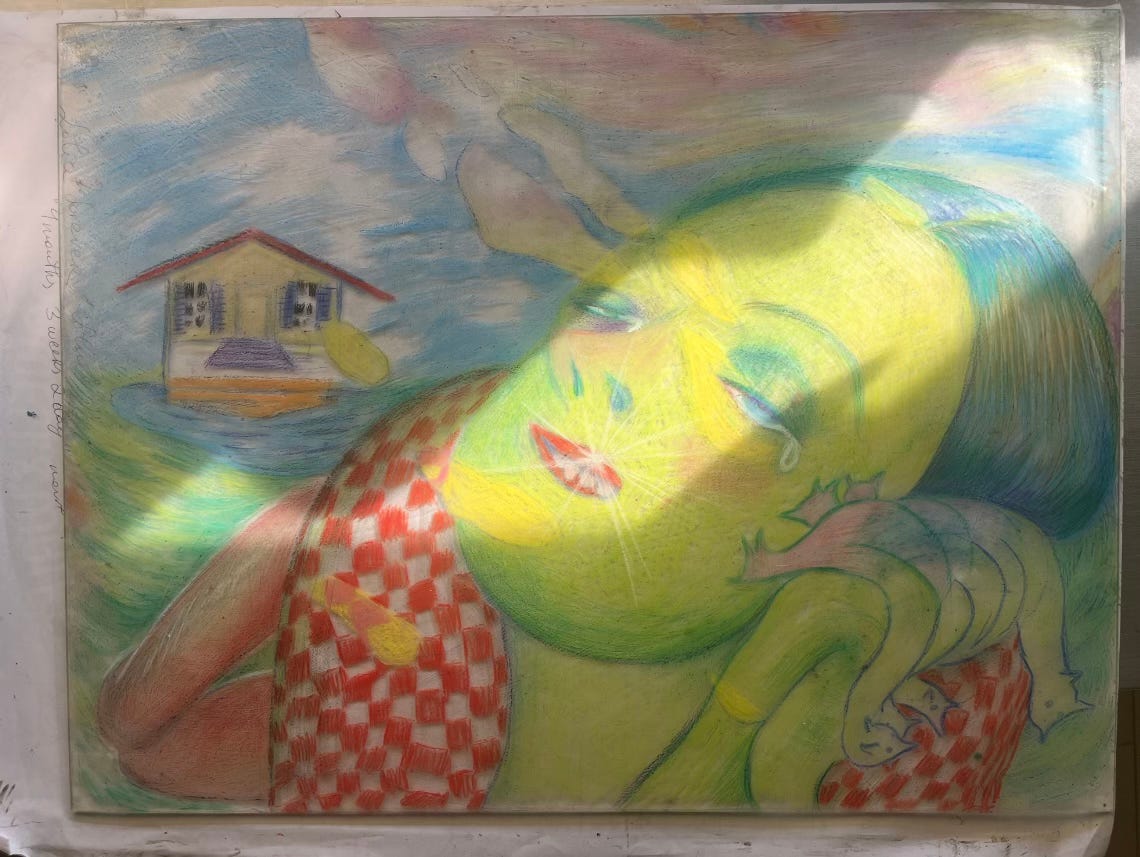

DS: The ideas of “what if” and “why not” are the driving forces. I am living vicariously through drawing.

It is interesting for me to learn that the subjects seem to be hedonistic, because I would argue that that is in the eye of a beholder rather than an intentional direction.

Bodies are a source of surprise and unfathomable possibilities (orifices as pockets, body parts as independent beings full of unique personalities and autonomy). Toilet humour in my drawings, for example, is, certainly, a vehicle that delivers childhood memories of jokes and such, and allows an adult mind (both mine and whoever else’s) to turn those into whatever adult mind turns them into.

MPM: It’s so funny because there are a number of Freudian interpretations you could surmise from your work like genitalia often appearing with a face or eyes, or cigarettes which certainly have oral, erotic connotations. Are you thinking of these types of connections or are these drawings simply streams of consciousness that you don’t bother interpreting while working?

DS: Body as a group portrait of individuals is something I thought of a while back. Each body part, full of personality and autonomy, is allowed to fight back unwanted attention. Also, so many many things have potential for erotic connotations and I like the idea that one, myself in this case, can be a benevolent creator who steps back allowing for things to be read into and interpreted as something other than what it is — a two-dimensional-nothing-much.

But, certainly, there is also the fact that for the first dozen drawings I did not notice certain gestures having certain possible connotations and then I suddenly did notice and continued to use them purposefully. So, yes, there is sometimes an element or a theme that becomes symbolic of something specific, but I would never disclose what.

MPM: Animals or anthropomorphic subjects are often portrayed in your work. Are these representations of our primal instincts, the unconscious, and the "wild" or "natural" aspects of the human psyche?

DS: Ha ha, maybe. My operational tactic is “what if . . . so and so took place”.

They are certainly representations of my instincts and the unconscious and the “wild” and the “natural”.

MPM: Can you talk a bit about how an artwork evolves? Do you work on several canvases simultaneously? What are your first steps in beginning a work?

DS: Not a single approach, really. Sometimes, there is a vision of an overall composition or of an action. Sometimes, it is a repetition of a theme that I approached a dozen times already or an exact same composition. Sometimes, it is a reaction to an abstract element within the support that I am using for the drawing, like a spot on the paper or a smudge, or a wrinkle in the canvas, or the random shapes in the hardground on the etching plate.

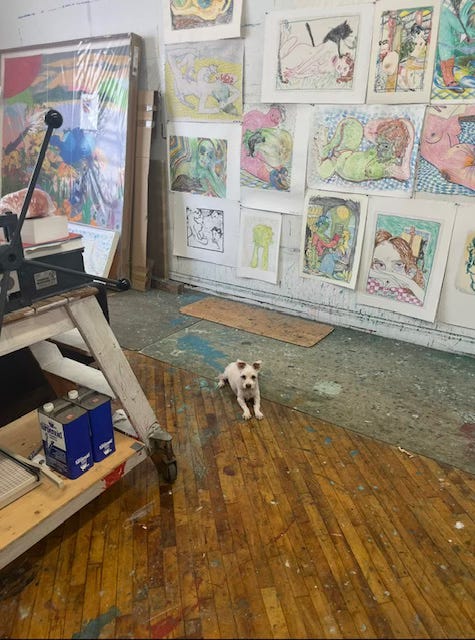

Often, I start on several surfaces at once, and then walk around the studio drawing. Few pieces on the walls, few on the tables. I end up getting involved with one more than with the others and bring it to fruition or, at least, to the point where I need to step away and draw somewhere else. With that said, I do like to submerge into a single image fully and finish with it before moving to the next, but it varies.

If I don’t have an idea of a composition then I begin with a single gesture (often found in the material, like a wrinkle that looks like an eye, for example). Then that single gesture calls for a follow up, an eye leads to a nose, nose leads to the rest of the face, etc., then the question pops “what would that face do?” and so on. And suddenly it is a picnic of ten people without pants, by the pond, in the hills. I draw from my head so things move quickly and the editing happens when the surface is quite full of information, resulting in the move to another surface all together.

MPM: For the group of monotypes that are included in the exhibition Bodies, I'm very interested in the process of how they were done. What was your process to create these exactly?

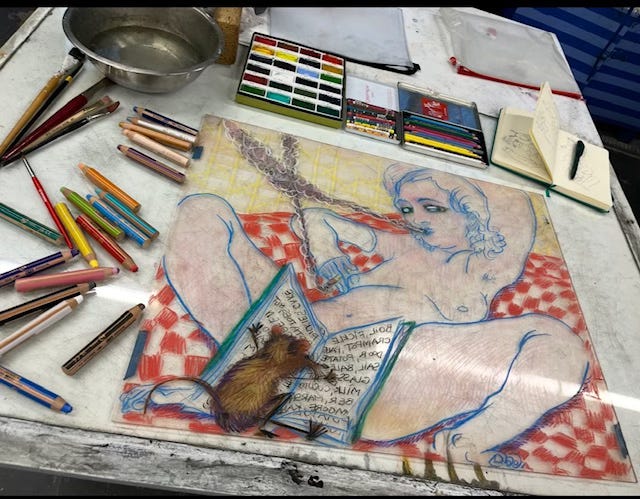

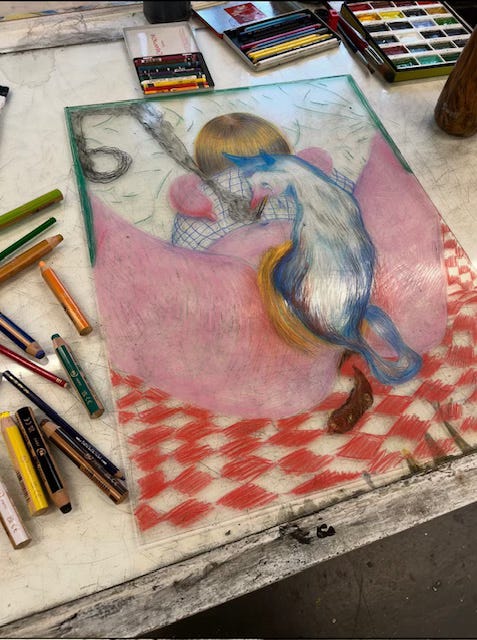

DS: Monotypes are a wonderful medium. It is very much a painting or drawing that relies on delayed gratification since the process of transferring the image from the plate onto paper needs to take place. In the case of my works, I have used water soluble pencils to create the pictures on plexiglass plates and transferred them onto damp paper using an etching press. Wetter paper can result in bleeding of colors, dropping of water onto the plate directly can result in a different kind of bleed marks, etc. So there is control and an element of surprise all at once.

It is quite satisfying to draw on a prepared plexi plate: pigments sit on the surface and they transfer onto paper in layers, or the marks can be made quite forcefully without any damage to the plate. It is, definitely, a special mental space – the work continues past the drawing stage and into the “pressing” and can continue even further into more drawing on the paper after the image has been transferred from the plate, etc.

Also, one can work into the ghost image left on the plate, creating a serial moment in the group of images.

MPM: On a final note, given our current administration's preoccupation with theocratic and authoritarian rule, do you feel that there are political interpretations to your work? Do you consider the hedonistic, decadent or nightmarish aspects of what is happening in your work a political position or statement?

DS: Life is a political act. A stream-of-consciousness drawing that is interpreted by another person as a “hedonistic relish of characters depicted” is very much an exercise in freedoms to choose to make the thing and to interpret the thing.

I find myself lacking language to express my horror and dismay and fear at the current administration’s actions and rhetoric. I am overwhelmed by the state of affairs in Ukraine, Russia, Palestine, Turkey, Hungary, Sudan, horrifically, one can go on and on listing lands on fire – it is fucked up!

So, yes, when language fails, one needs to express the rage, impotence, plan of action, revival, etc., in some way.

The work itself is not solving things, it is not even that much of a statement, but it is there as a personal act of defiance in the face of encroaching rule of you-name-it.

Lightness in the work is not about wistfulness or yearning for a better future, necessarily, but it could be about resilience to darkness in that very moment. Hope dies last.